Python Primer 🥳¶

The first chapter is about Python basics.

Python Overview¶

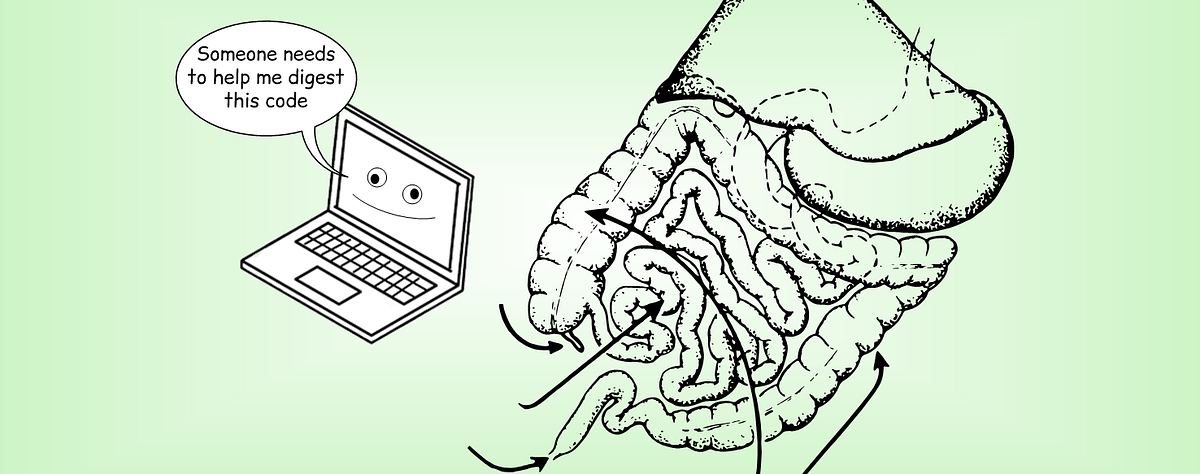

Python is formally an interpreted language (like PHP, Ruby, and JavaScript).

Commands are executed through a piece of software known as the Python interpreter.

The interpreter receives a command, evaluates that command, and reports the result of the command.

While the interpreter can be used interactively (especially when debugging), a programmer typically defines a series of commands in advance and saves those commands in a plain text file known as source code or a script. 😌

Interpreted vs Compiled¶

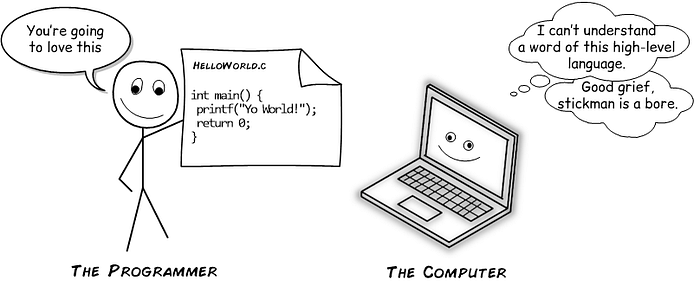

Both are translated into “computer language”, and the computer will be able to know what to do when he reads it (Computer speaks 0 and 1's). The difference is when/how you’ll translate it.

Plain C will not work. 😮

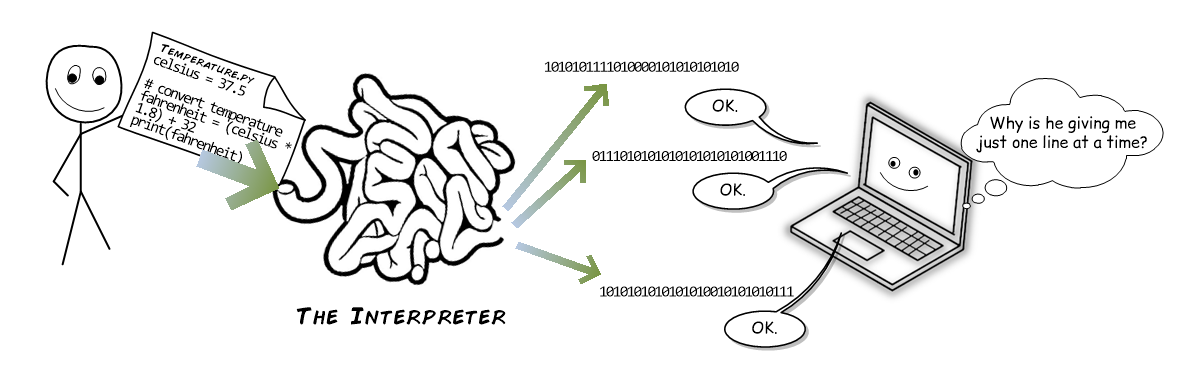

An interpreted language uses a software called interpreter to translate the original message into the “computer language”, much like a real life interpreter would translate somebody’s Portuguese speech into English in real time.

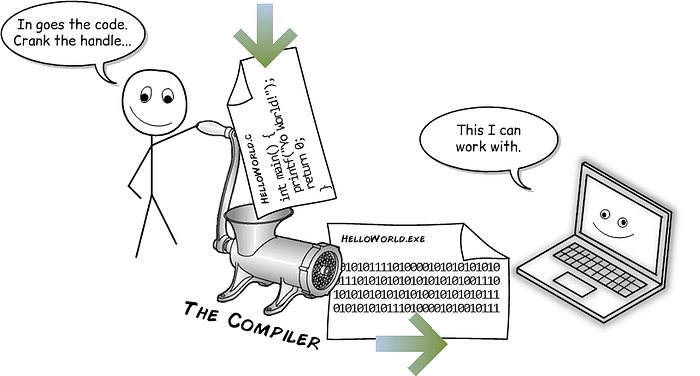

A compiled language uses a software called compiler that translates the original message and saves it to another file. You can imagine that the compiler would be the person creating subtitles for a speech.

The interpreter might come up with the translated message first, as he’s translating in real time, but if he’s asked to translate it again, he’ll have to redo the work every time.

The compiler on the other hand already did that work, and won’t have to repeat it since he saved it to a file. Also, it’s a lot easier for the compiler to optimize the message and make it more understandable to the computer, as he won’t need to hear the entire original message again.

Here are the Python Internal Workings:

-

Code Editor: Code Editor is the first stage of programs where we write our source code. This is human-readable code written according to Python’s syntax rules. It is where the execution of the program starts first.

-

Source code: The code written by a programmer in the code editor is then saved as a

.pyfile in a system. This file of Python is written in human-readable language that contains the instructions for the computer. -

Compilation Stage: The compilation stage of Python is different from any other programming language. Rather than compiling a source code directly into machine code. python compiles a source code into a byte code. In the compilation stage python compiler also checks for syntax errors. after checking all the syntax errors, if no such error is found then it generates a

.pycfile that contains bytecode. -

Python Virtual Machine (PVM) / Python Interpreter: The bytecode then goes into the main part of the conversion is the Python Virtual Machine (PVM). The PVM is the main runtime engine of Python. It is an interpreter that reads and executes the bytecode file, line by line. Here In the Python Virtual Machine translate the byte code into machine code which is the binary language consisting of 0's and 1's. The machine code is highly optimized for the machine it is running on. This binary language is only understandable by the CPU of a system.

-

Running Program: At last, the CPU executes the given machine code and the main outcome of the program comes as performing task and computation you scripted at the beginning of the stage in your code editor.

Python is an object-oriented language and classes form the basis for all data types.

In this section, we describe key aspects of Python’s object model, and we introduce Python’s built-in classes, such as the int class for integers, the float class for floating-point values, and the str class for character strings.

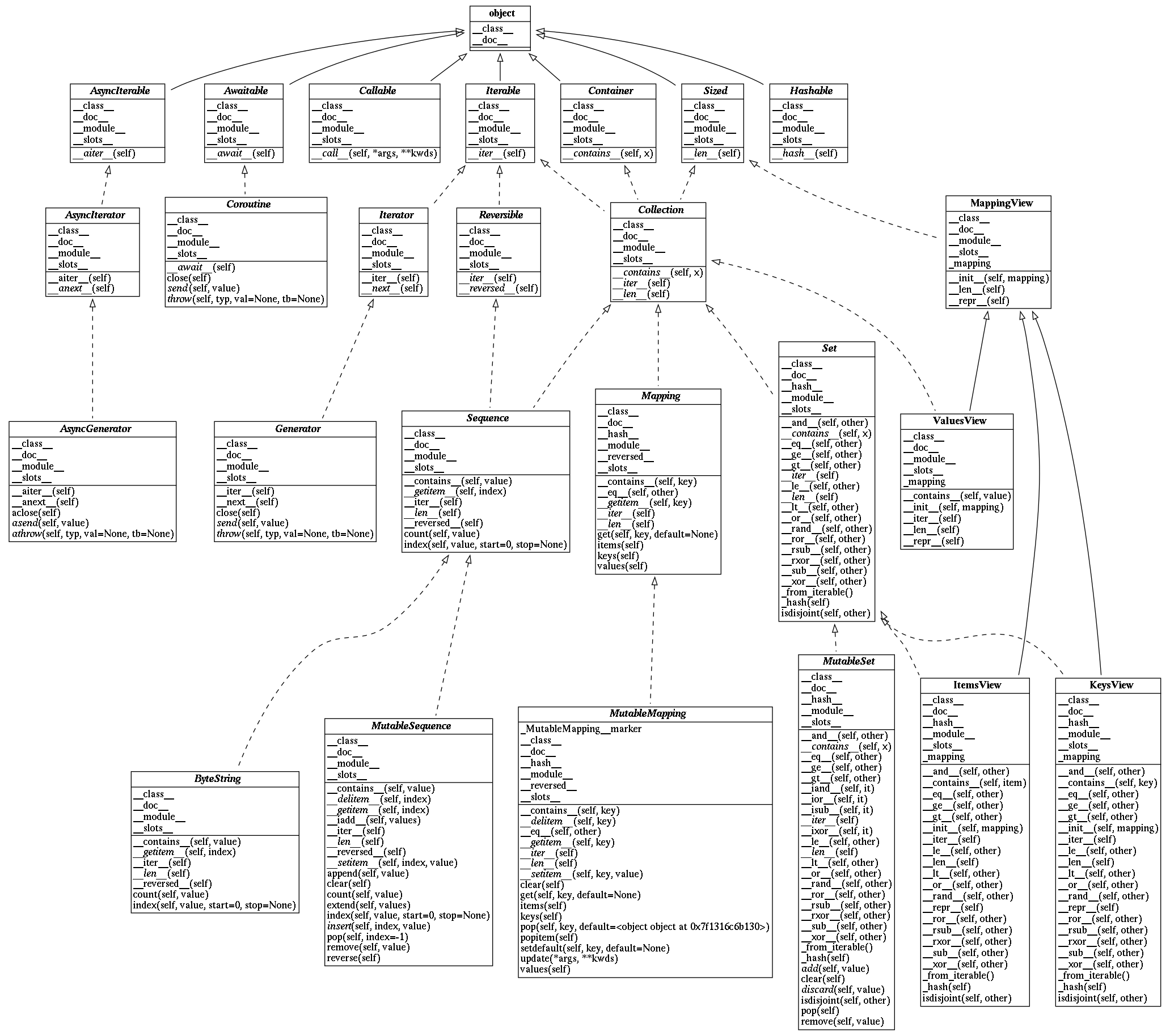

Here are some inheritance maps (possibly outdated) which data takes part of.

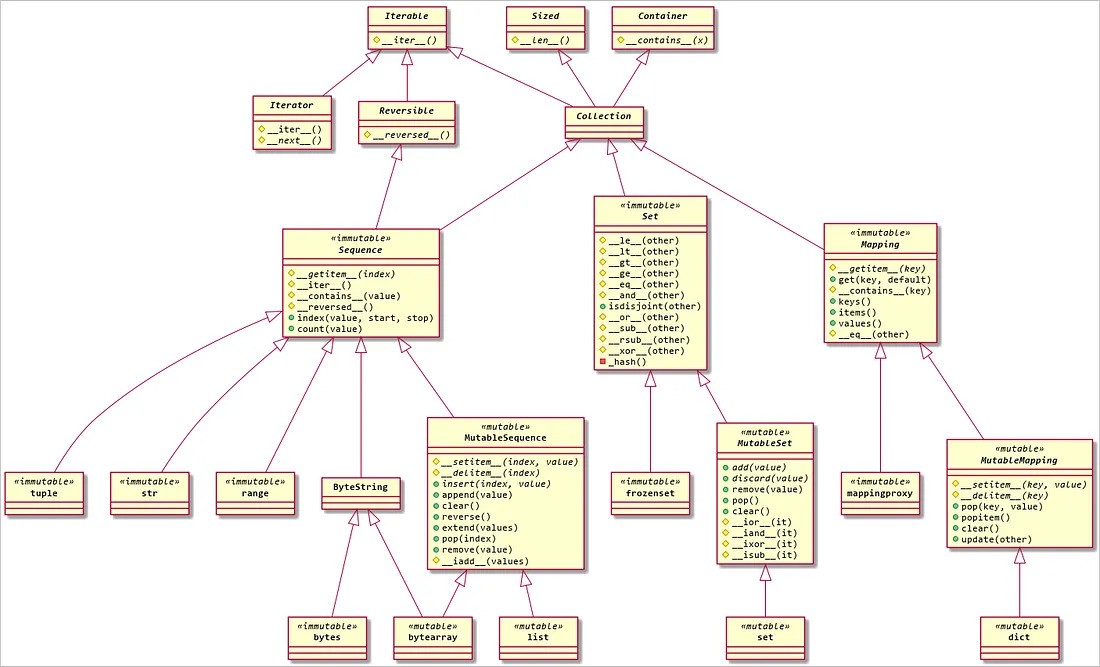

One more (possibly outdated too):

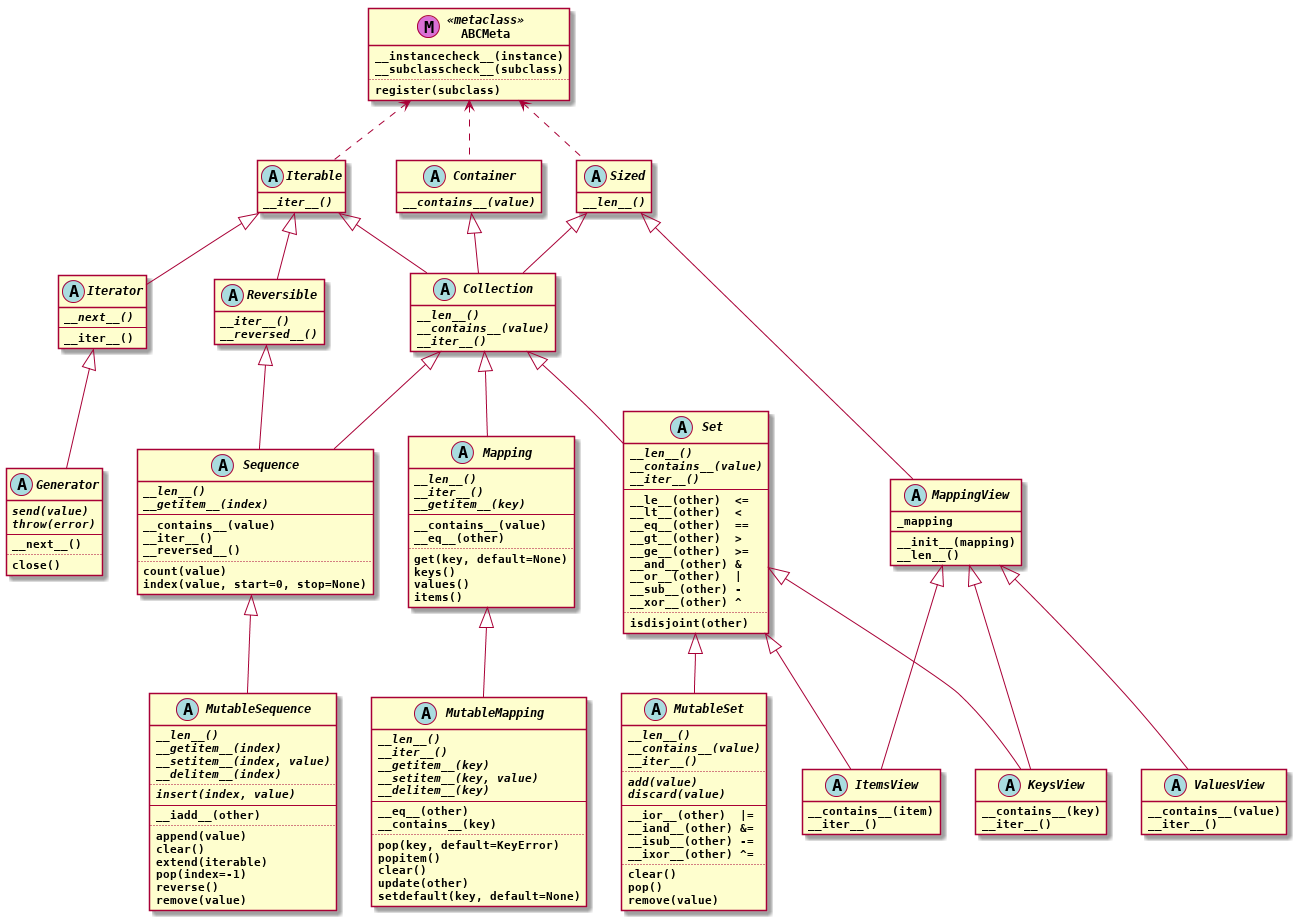

and another (possibly outdated too):

If you want to, you can think of the hierarchy from ancestor to child as : "Container - Collection - Sequence" 🥰

Strongly vs. Weakly Typed¶

Python is a strongly typed and dynamically typed language.

-

Dynamically typed means you don’t need to declare a variable’s type — the interpreter figures it out at runtime, and a variable can be reassigned to hold a different type of value.

-

Strongly typed means Python does not perform implicit type coercion. If you try to add a number to a string (

1 + "1"), Python will raise aTypeError.

In contrast, weakly typed languages like JavaScript often perform implicit type coercion. For example, 1 + "1" in JavaScript will result in "11" — converting the number to a string behind the scenes.

Strong typing in Python ensures type safety: you must explicitly convert types when needed, helping prevent subtle bugs.

Objects in Python 😎¶

In Python, everything you make, use, or reference is an instance of some class, and thus, it’s an object.

We'll dive deeper on this idea, but knowing it upfront might be good. 😌

Reserved Words¶

There are 33 specially reserved words that cannot be used as identifiers, as shown down below.

FalseascontinueelsefrominnotreturnyieldNoneassertdefexceptglobalisortryTruebreakdelfinallyiflambdapasswhileandclasselifforimportnonlocalraisewith

These are all reserved. This is just a simple reminder. 🥰

Python’s Built-In Classes 🤔¶

One thing we will talk about is immutability before we get to the common built-in classes.

A class is immutable if each object of that class has a fixed value upon instantiation that cannot subsequently be changed. For example, the float class is immutable.

Once an instance has been made, its value cannot be changed (although an identifier referencing that object can be reassigned to a different value).

| Class | Description | Immutable? |

|---|---|---|

| bool | Boolean value | + |

| int | integer (arbitrary magnitude) | + |

| float | floating-point number | + |

| list | mutable sequence of objects | |

| tuple | immutable sequence of objects | + |

| str | character string | + |

| set | unordered set of distinct objects | |

| frozenset | immutable form of set class | + |

| dict | associative mapping (aka dictionary) |

Why Immutability is important anyway? 🤔¶

Basically it comes down to the fact that immutability increases predictability, performance (indirectly) and allows for mutation tracking.

- Predictability:

Mutation hides change, which create (unexpected) side effects, which can cause nasty bugs. When you enforce immutability you can keep your application architecture and mental model simple, which makes it easier to reason about your application.

- Performance:

Even though adding values to an immutable Object means that a new instance needs to be created where existing values need to be copied and new values need to be added to the new Object which cost memory, immutable Objects can make use of structural sharing to reduce memory overhead.

All updates return new values, but internally structures are shared to drastically reduce memory usage (and Garbage Collection thrashing).

This means that if you append to a vector with 1000 elements, it does not actually create a new vector 1001-elements long. Most likely, internally only a few small objects are allocated.

- Mutation Tracking:

Besides reduced memory usage, immutability allows you to optimize your application by making use of reference- and value equality.

Easier to answer: "Did anything change?"

This makes it really easy to see if anything has changed.

Most Used Classes in Python 😍¶

The bool Class¶

Example: flag = True

Numbers evaluate to False if zero, and True if nonzero. Sequences and other container types, such as strings and lists, evaluate to False if empty and True if nonempty.

An important application of this interpretation is the use of a non boolean value as a condition in a control structure.

In Python, Boolean is a sub type of the integer type! 😯

The int Class¶

Example: my_number = 7

The int and float classes are the primary numeric types in Python.

The int class is designed to represent integer values with arbitrary magnitude.

Unlike Java and C++, which support different integral types with different precision (e.g., int, short, long), Python automatically chooses the internal representation for an integer based upon the magnitude of its value.

Typical literals for integers include 0, 137, and −23.

In some contexts, it is convenient to express an integral value using binary, octal, or hexadecimal. That can be done by using a prefix of the number 0 and then a character to describe the base.

Example of such literals are respectively: 0b1011, 0o52, and 0x7f.

The integer constructor, int(), returns value 0 by default.

But this constructor can be used to construct an integer value based upon an existing value of another type.

For example, if f represents a floating-point value, the syntax int(f) produces the truncated value of f. So both int(3.14) and int(3.99) produce the value 3, while int(−3.9) produces the value −3.

The constructor can also be used to parse a string that is presumed to represent an integral value (such as one entered by a user).

This is called Explicit type conversion which is also known as typecasting.

If s represents a string, then int(s) produces the integral value that string represents.

For example, the expression int("137") produces the integer value 137. If an invalid string is given as a parameter, as in int("hello") a ValueError is raised.

By default, the string must use base 10. If conversion from a different base is desired, that base can be indicated as a second, optional, parameter. For example, the expression int("7f", 16) evaluates to the integer 127.

The float Class¶

Example: my_float = 2.347

The float class is the sole floating-point type in Python, using a fixed-precision representation. Its precision is more similar to a double in Java or C++, rather than those languages’ float type.

We note that the floating-point equivalent of an integral number can be expressed directly as 2.0.

Technically, the trailing zero is optional, so some programmers might use the expression 2. to designate this floating-point literal.

One other form of literal for floating-point values uses scientific notation. For example, the literal 6.022e23 represents the mathematical value \(\(6.022 × 10^{23}\)\)

The constructor form of float() returns 0.0. When given a parameter, the constructor attempts to return the equivalent floating-point value.

For example, the call float(2) returns the floating-point value 2.0.

If the parameter to the constructor is a string, as with float("3,14"), it attempts to parse that string as a floating-point value, raising a ValueError as an exception.

Sequence Types: The list, tuple, and str Classes¶

The list, tuple, and str classes are sequence types in Python, representing a collection of values in which the order is significant.

The list class is the most general, representing a sequence of arbitrary objects (similar to an array in other languages).

The tuple class is an immutable version of the list class, benefiting from a streamlined internal representation.

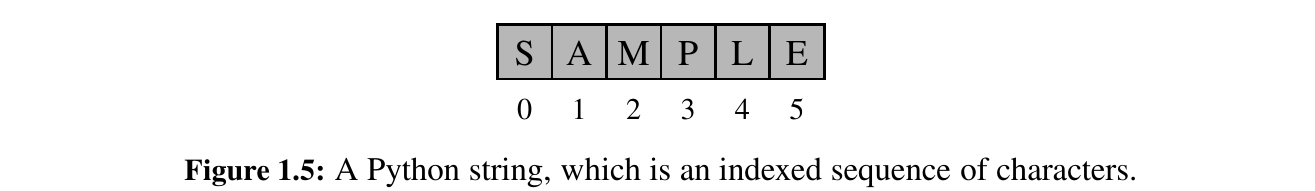

The str class is specially designed for representing an immutable sequence of text characters. We note that Python does not have a separate class for characters; they are just strings with length one.

The list Class¶

Example: my_list = ["a", "b", "c"]

A list instance stores a sequence of objects.

It's a referential structure, as it technically stores a sequence of references to its elements.

Elements of a list may be arbitrary objects (including the None object).

Lists are array-based sequences and are zero-indexed, thus a list of length n has elements indexed from 0 to n − 1 inclusive.

s = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

s[0:4:1] # [1, 2, 3, 4]

s[::-1] # reverses the list

del s[0] # 1 at 'index 0' is a goner.

# it will be gone when next gc.collect() triggers

# if this doesn't make sense, don't worry about it!

f = [1,2,3]

f.reverse()

print(f) # [3, 2, 1]

Lists are perhaps the most used container type in Python and they will be extremely central to our study of data structures and algorithms.

They have many valuable behaviors, including the ability to dynamically expand their capacities as needed (dynamic arrays).

Python uses the characters [] as delimiters for a list literal, with [] itself being an empty list.

As another example, ["red", "green", "blue"] is a list containing three string instances.

The contents of a list literal need not be expressed as literals, if identifiers a and b have been established, then syntax [a, b] is legitimate.

The list() constructor produces an empty list by default.

However, the constructor will accept any parameter that is of an iterable type.

We will discuss iteration further in this chapter, but examples of iterable types include all of the standard container types (e.g., strings, list, tuples, sets, dictionaries).

For example, the syntax list("hello") produces a list of individual characters, ["h", "e", "l", "l", "o"]. Also here is a cool thing:

Because an existing list is itself iterable, the syntax backup = list(data) can be used to construct a new list instance referencing the same contents as the original.

The tuple Class¶

Example: any_tuples_here = "?",

The tuple class provides an immutable version of a sequence, and therefore its instances have an internal representation that may be more streamlined than that of a list.

To express a tuple of length one as a literal, a comma must be placed after the element, but within the parentheses. For example, (17,) is a one-element tuple.

The reason for this requirement is that, without the trailing comma, the expression (17) alone is viewed as a simple parenthesized numeric expression (which would be an int). 😎

The str Class¶

Example: be = "the_spark"

Python’s str class is specifically designed to efficiently represent an immutable sequence of characters, based upon the Unicode international character set.

Strings have a more compact internal representation than the referential lists and tuples, as portrayed in Figure 1.5.

String literals can be enclosed in single quotes, as in 'hello' , or double quotes, as in "hello".

This choice is convenient, especially when using another of the quotation characters as an actual character in the sequence, as in "Don't stop".

Alternatively, the quote delimiter can be designated using a backslash as a so-called escape character, as in

Because the backslash has this purpose, the backslash must itself be escaped to occur as a natural character of the string literal, as in 'C:\\Python\\' , for a string that would be displayed as C:\Python\.

Other commonly escaped characters are "\n" for newline and "\t" for tab.

Unicode characters can be included, such as '20\u20AC' for the string 20€.

print("20 \u20AC ONLY!") # 20 € ONLY!

print("the escape room \'is real\'")

print("\'the numbers mason, what do they mean?\'")

Python also supports using the delimiter or """ to begin and end a string literal.

The advantage of such triple-quoted strings is that newline characters can be embedded naturally (rather than escaped as \n).

This can greatly improve the readability of long, multi line strings in source code. For example, rather than use separate print statements for each line of introductory output, we can use a single print statement, as follows:

print("""Welcome to the GPA calculator.

Please enter all your letter grades, one per line.

Enter a blank line to designate the end.""")

There are f-strings and r-strings in Python: Formatted Strings and Raw Strings

f-strings are a way to insert variables or expressions directly into a string in Python — and they’re fast and easy to read.

Here is an example of an f-string:

# is a equal to b?

a, b = 2, 3

print(f"{a} is not equal to {b}")

answer = "No"

print(f"The answer is {answer}")

Python raw string treats the backslash character \ as a literal character. Raw string is useful when a string needs to contain a backslash, such as for a regular expression or Windows directory path, and you don’t want it to be treated as an escape character.

Here is an example of on r-string from PyTorch: 💕

def reset_accumulated_memory_stats(device: Union[Device, int] = None) -> None:

r"""Reset the "accumulated" (historical) stats tracked by the CUDA memory allocator.

See :func:`~torch.cuda.memory_stats` for details. Accumulated stats correspond to

the `"allocated"` and `"freed"` keys in each individual stat dict, as well as

`"num_alloc_retries"` and `"num_ooms"`.

Args:

device (torch.device or int, optional): selected device. Returns

statistic for the current device, given by :func:`~torch.cuda.current_device`,

if :attr:`device` is ``None`` (default).

.. note::

See :ref:`cuda-memory-management` for more details about GPU memory

management.

"""

device = _get_device_index(device, optional=True)

return torch._C._cuda_resetAccumulatedMemoryStats(device)

The set and the Frozenset Classes¶

Examples: my_set = set([1,2,3]) , my_cold_set = frozenset((1,3))

Python’s set class represents the mathematical notion of a set, namely a collection of elements, without duplicates, and without an inherent order to those elements.

The major advantage of using a set, as opposed to a list, is that it has a highly optimized method for checking whether a specific element is contained in the set.

This is based on a data structure known as a hash table (which will be the primary topic of Chapter 10).

However, there are two important restrictions due to the algorithmic underpinnings.

-

The set does not maintain the elements in any particular order. However, after Python 3.6,

set.pop()become non random, so it pops items like Queues. -

The second is that only instances of immutable types (

hashable) can be added to a Python set. Therefore, objects such as integers, floating-point numbers, and character strings are eligible to be elements of a set.

It is possible to maintain a set of tuples, but not a set of lists or a set of sets, as lists and sets are mutable.

The frozenset class is an immutable form of the set type, so it is legal to have a set of frozensets.

Python uses curly braces {} as delimiters for a set, for example, as {17} or { "red" , "green" , "blue" }.

The exception to this rule is that {} does not represent an empty set; for historical reasons, it represents an empty dictionary (see next paragraph). Instead, the constructor syntax set() produces an empty set.

If an iterable parameter is sent to the constructor, then the set of distinct elements is produced.

For example, set("hello") produces {"h" ,"e" ,"l" ,"o" }.

Here are most used methods of sets:

s = set()

s.add(1) # add 1

s.add(2) # add 2

s.add(3) # add 3

s.discard(4) # No error

s.discard(4) # No error

# This will give a KeyError: 4

try:

s.remove(4)

except KeyError as e:

print(e) # 4

print(s) # {1, 2, 3}

print(3 in s) # True

print(4 not in s) # True

The dict Class¶

Example: my_dict = {"a" : 1, "b": 2}

Python’s dict class represents a dictionary, or mapping, from a set of distinct keys to associated values.

For example, a dictionary might map from unique student ID numbers, to larger student records (such as the student’s name, address, and course grades).

Python implements a dict using an almost identical approach to that of a set, but with storage of the associated values.

A dictionary literal also uses curly braces, and because dictionaries were introduced in Python prior to sets, the literal form {} produces an empty dictionary.

A nonempty dictionary is expressed using a comma-separated series of key:value pairs.

For example, the dictionary { "ga" : "Irish" , "de" : "German" } maps "ga" to Irish and "de" to German.

The constructor for the dict class accepts an existing mapping as a parameter, in which case it creates a new dictionary with identical associations as the existing one.

Alternatively, the constructor accepts a sequence of key-value pairs as a parameter:

Dictionaries iterate over their keys:

my_example_dict = {"Tokyo": 4, "Kyoto" : 6, "Osaka": 2}

for elem in my_example_dict:

print(elem, end = " ") # Tokyo Kyoto Osaka

Expressions, Operators, and Precedence¶

Existing values can be combined into larger syntactic expressions using a variety of special symbols and keywords known as operators.

The semantics of an operator depends upon the type of its operands.

For example, when a and b are numbers, the syntax a + b indicates addition, while if a and b are strings, the operator indicates concatenation.

In this section, we describe Python’s operators in various contexts of the built-in types.

Logical Operators¶

Python supports the following keyword operators for Boolean values:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

not |

unary negation |

and |

conditional and |

or |

conditional or |

Tip

The and and or operators short-circuit, in that they do not evaluate the second operand if the result can be determined based on the value of the first operand.

# All numbers evaluate to True

# All non empty sequences are True

# 0 and empty sequences are False

flag_1 = 1

flag_2 = 0

if flag_1 and flag_2:

print("both are true.")

if flag_1 or not flag_2:

print("Either flag_1 is True or flag_2 is false or both" )

Equality Operators:¶

Python supports the following operators to test two notions of equality:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

is |

same identity |

is not |

different identity |

** |

equivalent |

!= |

not equivalent |

a = 2

b = 2

print(a is b) # This is True only when a and b are aliases to same object

str_1 = "abc"

str_2 = "abc"

if str_1 == str_2:

print("This is True because these strings considered equivalent, because they match character to character.")

Tip

Wisdom: So in general, we use == or != , not identity (Identical objects are also equal but we rarely compare identical objects).

Comparison Operators:¶

Comparison happens lexicographically - Like Oxford Dictionary.

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

< |

less than |

<= |

less than or equal to |

> |

greater than |

>= |

greater than or equal to |

Tip

Comparisons should be between comparable operands.

Arithmetic Operators:¶

Python supports the following arithmetic operators:

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

+ |

addition |

− |

subtraction |

* |

multiplication |

/ |

true division |

// |

integer division |

% |

the modulo operator |

** |

power operator |

Tip

True division (/) implicitly converts the data type to float.

a = 3

b = 4

c = 7.8

d = 12 * 10 ** 3

f = 12

g = ((3 ** 2) + (4 ** 2)) ** 0.5

print(a // b) # 0 because it is rounded

print(7 // 3) # 2

print(7 // 4) # 1

print(a / b) # 0.75 - result is a float

print(isinstance((lambda x: x / 2)(2), float)) # True

print(int(0.75)) # 0, as expected

print(c / b) # 1.95, a float

print(56 % 10) # 6

print(d % f) # 0 because this is the remainder

print([[(10 % 3) * 10] for _ in range(3)]) # [[10], [10], [10]]

print(g) # 5.0 - the great triangle

print(5 ** 2 ** 2) # 625

print(divmod(d, f)) # (1000, 0) - tuple of (quotient, remainder)

print(divmod(10,3)) # 3, 1

print(divmod(10,5)) # 2, 0

#

# dividend | divisor

# |________

# _________| quotient

# remainder|

# |

Tangent: Is Instance - Functions and Callable 🐘¶

This part is only for the curious, not required right now 😌

if isinstance((lambda x : x // 2), function):

print("yeah that is a function!") # this does not work!

This gives error. Why? 🤔

The isinstance function takes two arguments: an object and a class or a tuple of classes.

It checks whether the object is an instance of the specified class or classes.

In your case, you're trying to check whether a lambda function is an instance of the function class, but lambdas are not directly instances of the function class in Python.

To check if an object is callable (i.e., a function), you can use the callable() function. Here's how you can correct your code:

is every callable a function?¶

Not necessarily. While all functions are callable objects in Python, not all callable objects are functions.

In Python, callable objects include:

- Functions defined using the

defkeyword. - Functions defined using the

lambdakeyword. - Built-in functions provided by Python.

- Methods of classes.

- Classes (if they define a

__call__()method). - Instances of classes that implement the

__call__()method.

However, not all callable objects are functions.

For example, classes can be callable if they define a __call__() method, but they are not traditional functions.

Similarly, instances of classes that implement the __call__() method are callable, but they may not be considered functions in the traditional sense.

is every function callable?¶

Yes, in Python, every function is callable.

When you define a function using the def keyword or with a lambda expression using the lambda keyword, the resulting object is callable.

This means you can execute the function by using parentheses () after its name, passing any required arguments.

Bitwise Operators¶

Back to our topic 🍓

This is a wonderful source on bitwise operators.

You can use bitwise operators to perform Boolean logic on individual bits. That’s analogous to using logical operators such as and, or, and not, but on a bit level.

Bitwise operators were used a lot more in programming when computers didn’t have as much memory in them as they do now.

Bitwise operators are still used for those working on embedded devices that have memory limitations.

Python provides the following bitwise operators for integers:

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

∼ |

bitwise complement (prefix unary operator) |

& |

bitwise and |

pipe |

bitwise or |

ˆ |

bitwise exclusive-or |

<< |

shift bits left, filling in with zeros |

>> |

shift bits right, filling in with sign bit |

Bitwise And:

Two things to know:

x & 1 == x for x == 0 or x== 1 - And with 1 is bit itself.

# Bitwise AND operator

a = 10 # = 1010 (Binary)

b = 4 # = 0100 (Binary)

c = a & b # 1010

# 0100

# &____

# 0000

# 0 (Decimal)

print(c) # 0

d = 156 # 10011100

f = 52 # 00110100

# &________

# 00010100

# which is 20 decimal

g = d & f

print(g) # 20

Bitwise Or:

Two things to know:

x | 0 = x for x ** 0 or x ** 1 - Or with 0 is the number itself.

# Bitwise OR operator

k = 44 # 101100

l = 13 # 001101

# |______

# 101101

# which is 45 decimal

m = k | l

print(m) # 45

Bitwise XOR - The apple Operator. 🍎

I call this the Apple operator because at Apple, people from diverse backgrounds do amazing things.

Two of the same just makes 0, nothing new.

XOR of a Number with Itself: number ^ number = 0 - number can be multiple digits:

- This property is a fundamental characteristic of XOR.

- If you XOR a value with itself, all corresponding bits will cancel each other out, resulting in zero.

XOR of a Number with 0: number ^ 0 = number - number can be multiple digits:

- XOR'ing any value with zero leaves the value unchanged.

- This is because XOR compares corresponding bits, and if one of them is zero, the result will be the other bit.

# Bitwise XOR -

# same makes 0 different makes 1

# if you xor a number with itself, the result will be 0

ma = 7

mb = ma ^ ma

print(mb) # 0

print(ma ^ 0) # 7 because eveything will be the same as the number.

# if you xor a number with 0 the result will be number itself

n = 11 # 1011

o = 3 # 0011

# ^____

# 1000

# which is 8 in decimal

p = n ^ o

print(p) # 8

Bitwise NOT

# Bitwise NOT

# Performs A logical negation on a given number

# by flipping all of its bits.

r = 156 # 10011100

# ~

# 01100011

print(~r) # it says -157. hmmm

# instead AND with 255

s = ~r & 0b11111111

print(s) # this will be 99. Which we originally expected.

Bitwise Shift - Left and Right Shift explained below.

Left Shift

# Bitwise Shift

# Left Shift

# Moves the bits to left, filling with zero:

a = 39 # 39 000100111

print(a << 1) # 78 001001110

print(a << 2) # 156 010011100

print(a << 3) # 312 100111000

Bit masks ?¶

On paper, the bit pattern resulting from a left shift becomes longer by as many places as you shift it. That’s also true for Python in general because of how it handles integers.

However, in most practical cases, you’ll want to constrain the length of a bit pattern to be a multiple of eight, which is the standard byte length.

For example, if you’re working with a single byte, then shifting it to the left should discard all the bits that go beyond its left boundary:

It’s sort of like looking at an unbounded stream of bits through a fixed-length window.

There are a few tricks that let you do this in Python. For example, you can apply a bitmask with the bitwise AND operator:

Shifting 39 by three places to the left returns a number higher than the maximum value that you can store on a single byte.

It takes nine bits, whereas a byte has only eight.

To chop off that one extra bit on the left, you can apply a bitmask with the appropriate value.

If you’d like to keep more or fewer bits, then you’ll need to modify the mask value accordingly.

Right Shift

# Bitwise Right Shift

# Pushes bits to right, rightmost bit drops

a = 157 # 10011101 - 157

print(a >> 1) # 01001110 78

print(a >> 2) # 00100111 39

print(a >> 3) # 00010011 19

Tip

You can further categorize the bitwise shift operators as arithmetic and logical shift operators.

While Python only lets you do the arithmetic shift, it’s worthwhile to know how other programming languages implement the bitwise shift operators to avoid confusion and surprises.

This distinction comes from the way they handle the sign bit, which ordinarily lies at the far left edge of a signed binary sequence.

In practice, it’s relevant only to the right shift operator, which can cause a number to flip its sign, leading to integer overflow.

Sequence Operators:¶

Each of Python’s built-in sequence types (str, tuple, and list) support the following operator syntaxes:

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

s[j] |

element at index j |

s[start:stop] |

slice including indices [start,stop) |

s[start:stop:step] |

slice starting from start with step, not equal to stop |

s + t |

concatenation of sequences |

k * s |

shorthand for s + s + s + ... (k times) |

val in s |

containment check |

val not in s |

non-containment check |

my_seq = [7, 8, 9]

print(my_seq[1:2]) # 8

print(my_seq[0:3:2]) # [7, 9]

print(my_seq + ["a", "b", "c"]) # [7, 8, 9, 'a', 'b', 'c']

print(my_seq + [["a", "b", "c"][-1]]) # [7, 8, 9, 'c']

result = [0] * 4 # [0, 0, 0, 0]

print(0 in result) # True

Python uses zero indexing in sequences. Also we can access elements with negative indexes.

Index -1 denotes the last element in a sequence. 🥰

Sequences define comparison operations based on lexicographic order, performing an element by element comparison until the first difference is found.

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

s ** t |

equivalent (element by element) |

s != t |

not equivalent |

s < t |

lexicographically less than |

s <= t |

lexicographically less than or equal to |

s > t |

lexicographically greater than |

s >= t |

lexicographically greater than or equal to |

Operators for Sets and Dictionaries:¶

Sets¶

They do not provide order between elements, so comparison is not lexicographic. No orders here.

Also there is no slicing for sets. Sets and frozensets support the following operators:

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

key in s |

containment check |

key not in s |

non-containment check |

s1 ** s2 |

s1 is equivalent to s2 |

s1 != s2 |

s1 is not equivalent to s2 |

s1 <= s2 |

s1 is subset of s2 |

s1 < s2 |

s1 is proper subset of s2 |

s1 >= s2 |

s1 is superset of s2 |

s1 > s2 |

s1 is proper superset of s2 |

s1 pipe s2 |

the union of s1 and s2 |

s1 & s2 |

the intersection of s1 and s2 |

s1 − s2 |

the set of elements in s1 but not s2 |

s1 ˆ s2 |

the set of elements in precisely one of s1 or s |

hset = {1 , 2 , 3, 4}

hset_2 = {6, 7, 9, 4}

hset_3 = {1, 2, 3}

print(f" is {2} in the hset: {2 in hset}") # True

# is 2 in the hset: True

# print([] in hset) # unhashable type: 'list'

print(f" is {7} in the hset: {7 in hset}") # False

# is 7 in the hset: False

print(f"are these equal: {hset ** hset_2}" ) # False

# are these equal: False

print(f" smaller or equal ? : {hset <= hset_2}") # False

# smaller or equal ? : False

print( hset < hset_2 ) # False

print( hset >= hset_3 ) # True

print( hset > hset_3 ) # True

print( hset | hset_2 ) # {1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9}

print( hset & hset_2 ) # {4}

print(f"The difference between big number set and small number set: {hset_2 - hset}")

# The difference between big number set and small number set: {9, 6, 7}

# only in set 1 OR set 2

print(hset ^ hset_2) # {1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9}

hset.add(12)

hset.remove(12)

hset.discard(7) # does not give an error even though 7 is not in the set

Dictionaries¶

Do not maintain a well defined order on their elements. O(1) access to elements. 😍

| operator | meaning |

|---|---|

d[key] |

value associated with given key |

d[key] = value |

set (or reset) the value associated with given key |

del d[key] |

remove key and its associated value from dictionary |

key in d |

containment check |

key not in d |

non-containment check |

d1 ** d2 |

d1 is equivalent to d2 |

d1 != d2 |

d1 is not equivalent to d2 |

hmap = {"gary" : 1, "alex": 3, "artour" : 7, "greg": 10, "andrej": 20}

print(hmap["gary"]) # 1

print(hmap.get("alexx", 100)) # 100

print("artour" in hmap) # True

print(hmap ** {True: 1}) # False

print(max(hmap)) # "greg" - biggest key, literally

print(max(hmap, key=hmap.get)) # andrej - key for max changed

Extended Assignment Operators¶

For an immutable type, such as a number or a string, one should not presume that this syntax changes the value of the existing object, but instead that it will reassign the identifier to a newly constructed value.

Immutables will be made as new objects!

However, it is possible for a type to redefine such semantics to mutate the object, as the list class does for the += operator.

"""

We can do the following to all mutable values - list - set - dict

"""

alpha = [1, 2, 3]

beta = alpha # an alias for alpha

beta += [4, 5] # extends the original list with two more elements

beta = beta + [6, 7] # reassigns beta to a new list [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

print(alpha) # will be [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(beta) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Operator Precedence¶

Programming languages must have clear rules for the order in which compound expressions, such as (5 + 2 * 3), are evaluated.

Higher precedence will be executed first.

| Precedence | Type | Symbols |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | member access | expr.member |

| 2 | function/method calls | expr(...) |

| 2 | container subscripts/slices | expr[...] |

| 3 | exponentiation | ** |

| 4 | unary operators | +expr, −expr, ̃expr |

| 5 | multiplication, division | star, /, //, % |

| 6 | addition, subtraction | +, − |

| 7 | bitwise shifting | <<, >> |

| 8 | bitwise-and | & |

| 9 | bitwise-xor | ˆ |

| 10 | bitwise-or | pipe |

| 11 | comparisons | is, is not, **, !=, <, <=, >, >= |

| 11 | containment | in, not in |

| 12 | logical-not | not expr |

| 13 | logical-and | and |

| 14 | logical-or | or |

| 15 | conditional | val1 if cond else val2 |

| 16 | assignments | =, +=, −=, =, etc |

Control Flow 🌠¶

Now let's discover the control flow 🎶

Conditionals¶

Most fundamental control structures are conditional statements and loops.

The colon character : is used to delimit the beginning of a block of code that acts as a body for a control structure.

If the body can be stated as a single executable statement, it can technically be placed on the same line, to the right of the colon.

if condition:

first_body:

elif second_condition:

second_body:

else:

last_body

if seq:

print("This means seq is not Empty")

# we can do nested

if door_is_closed:

if door_is_locked:

unlock()

open_door()

move()

Loops¶

Python offers two distinct looping constructs.

A while loop allows general repetition based upon the repeated testing of a Boolean condition.

A for loop provides convenient iteration of values from a defined series (such as characters of a string, elements of a list, or numbers within a given range).

While loops - Use when not sure of the loop count¶

while condition:

body

l = 10

while l >= 0:

print(f"l is decreasing, be careful. Current Value {l}")

l -= 1

# another example

from collections import deque

j = deque()

for i in range(1,10,2):

j.append(i)

while j:

# empty the queue

print(j.popleft())

The execution of a while loop begins with a test of the Boolean condition. If that condition evaluates to True, the body of the loop is performed.

After each execution of the body, the loop condition is retested, and if it evaluates to True, another iteration of the body is performed.

When the conditional test evaluates to False (assuming it ever does), the loop is exited and the flow of control continues just beyond the body of the loop.

For loops - Use when a specific limit is apparent¶

Python’s for-loop syntax is a more convenient alternative to a while loop when iterating through a series of elements.

The for-loop syntax can be used on any type of iterable structure, such as a list, tuple, str, set, dict, or file (we will discuss iterators more formally in Chapter 1.8). 😌

Its general syntax appears as follows.

In this case, identifier j is not an element of the data—it is an integer. But the expression data[j] can be used to retrieve the respective element.

For example, we can find the index of the maximum element of a list as follows:

Break and Continue Statements¶

Python supports a break statement that immediately terminate a while or for loop when executed within its body.

More formally, if applied within nested control structures, it causes the termination of the most immediately enclosing loop.

As a typical example, here is code that determines whether a target value occurs in a data set:

Python also supports a continue statement that causes the current iteration of a loop body to stop, but with subsequent passes of the loop proceeding as expected.

Functions 🥰¶

There are functions and methods. We begin with an example to demonstrate the syntax for defining functions in Python.

The following function counts the number of occurrences of a given target value within any form of iterable data set.

def count(data, target): # function signature

"""Count the occurance of target in data"""

# body of the function

n = 0

for item in data:

if item ** target: # found a match

n += 1

return n

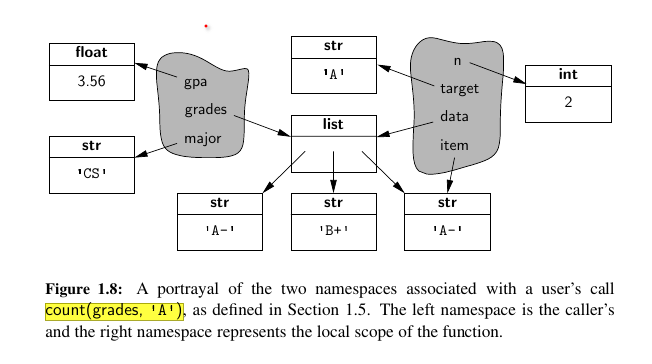

Each time a function is called, Python creates a dedicated activation record that stores information relevant to the current call. This activation record includes what is known as a namespace to manage all identifiers that have local scope within the current call.

The namespace includes the function’s parameters and any other identifiers that are defined locally within the body of the function.

An identifier in the local scope of the function caller has no relation to any identifier with the same name in the caller’s scope (although identifiers in different scopes may be aliases to the same object).

In our first example, the identifier \(n\) has scope that is local to the function call, as does the identifier item, which is established as the loop variable.

Return Statement¶

A return statement is used within the body of a function to indicate that the function should immediately cease execution, and that an expressed value should be returned to the caller.

If a return statement is executed without an explicit argument, the None value is automatically returned. Likewise, None will be returned if the flow of control ever reaches the end of a function body without having executed a return statement.

Type Hints¶

Consider the function:

def dollar_to_euro_with_default(dollar_amount, conversion_rate=0.93):

return dollar_amount * conversion_rate

Notice that we can pass in any type we want as function arguments, even if the function written to work only with a certain type.

For example, Python will let us call dollars_to_euros_with_default(True, "abc"), but it will then fail because multiplication isn't defined between bools and strings.

We can add type hints to our functions to help with this.

This is done by adding a colon, an optional space, and a data type to a parameter like dollar_amount: float .

The return type is indicated with a hyphen, a greater than sign, and data type before the colon at the end of the signature line. -> str.

Documentation in Functions¶

We gotta use dostrings for fellow humans, and ourselves.

def dollar_to_euro_with_default(dollar_amount: float,

conversion_rate: float = 0.93) -> float:

"""

Returns Dollar amount to Euros based on a conversion rate

Parameters:

dollar_amount (float): Dollar amount to be converted to euros

conversion_rate (float): Dollar to Euro conversion rate. Default:0.93

Returns:

euro_amount (float): Euro equivalent of Dollar amount based on conversion rate

"""

euro_amount = dollar_amount * conversion_rate

return euro_amount

These are special, because we can run the following thanks to docstrings:

help(dollar_to_euro_with_default)

# this is not dollar_to_euro_with_default()

# because we are NOT calling the function, we are referencing the function itself

Information Passing¶

In the context of a function signature, the identifiers used to describe the expected parameters are known as formal parameters, and the objects sent by the caller when invoking the function are the actual parameters.

Parameter passing in Python follows the semantics of the standard assignment statement.

When a function is invoked, each identifier that serves as a formal parameter is assigned, in the function’s local scope, to the respective actual parameter that is provided by the caller of the function.

def sum_of_ints(a: int, b: int, c: int): -> int

return (a + b + c)

sum_of_ints(1, 3, 4)

# actual parameters 1, 3 and 4 are assigned to formal parameters

# a, b, c in the functions local scope.

An advantage to Python’s mechanism for passing information to and from a function is that objects are not copied. This ensures that the invocation of a function is efficient, even in a case where a parameter or return value is a complex object.

Pass By Value or Pass By Reference?¶

You will hear this on different programming languages too. Let's discover what it means. 🐑

Immutable Objects (Pass by Value-Like):¶

- For immutable objects like

integers,floats,strings, andtuples, Python behaves in a way that is similar to "pass by value" in other languages. - When you pass an immutable object to a function, a copy of the object's value is passed, and modifications made inside the function do not affect the original object.

def modify_value(x):

x += 1

print("Inside function:", x)

num = 5

modify_value(num)

print("Outside function:", num)`

# Inside function: 6

# Outside function: 5

Mutable Objects (Pass by Reference-Like):¶

- For mutable objects like

listsanddictionaries, Python behaves in a way that is more like "pass by reference." - When you pass a mutable object to a function, you are passing a reference to the original object. Modifications made inside the function are visible outside, as both the function and the caller are working with the same object.

def modify_list(my_list):

my_list.append(42)

original_list = [1, 2, 3]

modify_list(original_list)

print(original_list) # [1, 2, 3, 42]

Tip

In Python is that when you pass an object to a function, you are passing a reference to that object. For mutable objects, changes made inside the function are visible outside. For immutable objects, the behavior is similar to passing by value because modifications inside the function don't affect the original object.

Default Parameter Values¶

Python provides means for functions to support more than one possible calling signature. Such a function is said to be polymorphic (which is Greek for “many forms”).

Most notably, functions can declare one or more default values for parameters, thereby allowing the caller to invoke a function with varying numbers of actual parameters. As an artificial example, if a function is declared with signature def foo(a, b=15, c=27): there are three parameters, the last two of which offer default values.

Keyword Parameters¶

The traditional mechanism for matching the actual parameters sent by a caller, to the formal parameters declared by the function signature is based on the concept of positional arguments.

For example, with signature foo(a=10, b=20, c=30), parameters sent by the caller are matched, in the given order, to the formal parameters.

An invocation of foo(5) indicates that a=5, while b and c are assigned their default values.

Python supports an alternate mechanism for sending a parameter to a function known as a keyword argument.

A keyword argument is specified by explicitly assigning an actual parameter to a formal parameter by name. For example, with the above definition of function foo, a call foo(c=5) will invoke the function with parameters a=10, b=20, c=5.

Special Methods - Dunders For Classes:¶

They are methods with double underscores before and after their name — like __init__, __str__, __len__.

📛 That’s why they’re called dunders = "double underscores". You can do magical things with it.

class Watch:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

def __getitem__(self, key):

# [] access

# Implement custom behavior for accessing items with square brackets

return self.data[key]

def get(self, key, default=None):

# Implement custom behavior for the get method

return self.data.get(key, default)

def __delitem__(self, key):

# Implement custom behavior for deleting items

del self.data[key]

def __contains__(self, key):

# Implement custom behavior for containment check

return key in self.data

def __eq__(self, other):

# Implement custom behavior for equality check

return self.data ** other.data

def __ne__(self, other):

# Implement custom behavior for non-equality check

return not self.__eq__(other)

# Example Usage

watch_data = {"key1": "value1", "key2": "value2", "key3": "value3"}

# Create instances of Watch with the dictionary

watch1 = Watch(watch_data)

watch2 = Watch({"key1": "value1", "key2": "value2", "key3": "value3"})

# getitem method

# Access values using square bracket notation

print(watch1["key1"]) # Output: value1

# Use the custom get method

print(watch1.get("key1", 0)) # Output: value1

# Delete an item

del watch1["key1"]

print("After deletion:", watch1.data) # Output: {'key2': 'value2', 'key3': 'value3'}

# Containment check

print("key2" in watch1) # Output: True

print("nonexistent_key" in watch1) # Output: False

# Equality check

print(watch1 ** watch2) # Output: True

# Non-equality check

print(watch1 != watch2) # Output: False

Python’s Built-In Functions¶

Here are almost all the built in functions in Python. You can use this as a reference.

| Common Built-In Functions | |

|---|---|

| Calling Syntax | Description |

abs(x) |

Return the absolute value of a number. |

all(iterable) |

Return True if bool(e) is True for each element e. |

any(iterable) |

Return True if bool(e) is True for at least one element e. |

bin(integer) |

Convert an integer number to a binary string prefixed with “0b” |

callable(object) |

Return True if the object argument appears callable, False if not. |

chr(integer) |

Return a one-character string with the given Unicode code point. |

dir(object) |

Without arguments, return the list of names in the current local scope. With an argument, attempt to return a list of valid attributes for that object. |

divmod(x, y) |

Return (x // y, x % y) as tuple, if x and y are integers. |

enumerate(iterable, start=0) |

Return an enumerate object. iterable must be a sequence, an iterator, or some other object which supports iteration. |

filter(function, iterable) |

Returns an iterator where the items are filtered through a function to test if the item is accepted or not. |

hash(obj) |

Return an integer hash value for the object (see Chapter 10). |

hex(number) |

Return the hexadecimal representation string of a given number, prefixed with "0x" |

id(obj) |

Return the unique integer serving as an “identity” for the object. |

input(prompt) |

Return a string from standard input; the prompt is optional. |

isinstance(obj, cls) |

Determine if obj is an instance of the class (or a subclass). |

iter(iterable) |

Return a new iterator object for the parameter (see Chapter 1.8). |

len(iterable) |

Return the number of elements in the given iteration. |

map(f, iter1, iter2, ...) |

Return an iterator yielding the result of function calls \(f(e1, e2, ...)\) for respective elements \(e1 ∈ iter1\), \(e2 ∈ iter2\), ... |

max(iterable) |

Return the largest element of the given iteration. |

max(a, b, c, ...) |

Return the largest of the arguments. |

min(iterable) |

Return the smallest element of the given iteration. |

min(a, b, c, ...) |

Return the smallest of the arguments. |

next(iterator) |

Return the next element reported by the iterator (see Chapter 1.8). |

oct(x) |

Convert an integer number to an octal string prefixed with “0o”. |

open(filename, mode) |

Open a file with the given name and access mode. |

ord(char) |

Return the Unicode code point of the given character (length = 1 string). |

pow(x, y) |

Return the value x^y (as an integer if x and y are integers), equivalent to x ** y. |

pow(x, y, z) |

Return the value (x^y mod z) as an integer. |

print(obj1, obj2, ...) |

Print the arguments, with separating spaces and trailing newline. |

range(stop) |

Construct an iteration of values \(0, 1, . . . , stop − 1\). |

range(start, stop) |

Construct an iteration of values \(start, start + 1, . . . , stop − 1\). |

range(start, stop, step) |

Construct an iteration of values \(start, start + step, start + 2 * step\), . . . |

reversed(sequence) |

Return an iteration of the sequence in reverse. |

round(x) |

Return the nearest int value (a tie is broken toward the even value). |

round(x, k) |

Return the value rounded to the nearest \(10^{−k}\) (return-type matches x). |

sorted(iterable) |

Return a list containing elements of the iterable in sorted order. |

sum(iterable) |

Return the sum of the elements in the iterable (must be numeric). |

type(obj) |

Return the class to which the instance obj belongs. |

vars(object) |

Return the __dict__ attribute for a module, class, instance, or any other object with a __dict__ attribute. |

zip(iterables, strict = False) |

Iterate over several iterables in parallel, producing tuples with an item from each one. |

Continuing from __iter__:

Continuing from min():

Continuing from with:

All the ones that we missed:

class C:

def __init__(self):

self._x = None

self.__y = 2

def getx(self):

return self._x

def setx(self, value):

self._x = value

def delx(self):

del self._x

x = property(getx, setx, delx, "I'm the 'x' property.")

myc = C()

print(vars(myc)) # {'_x': None, '_C__y': 2}

These might be useful to understand the basics.

For even more examples check the official documentation 💕

Simple I/0 🤔¶

Programs are part of a bigger system — and sometimes, that means interacting directly with the user.

Console I/O¶

The primary means for acquiring information from the user console is a built-in function named input().

input() is always a string.

We've also seen the print() function.

print() has a lot of cools stuff. One of them is f-strings.

• By default, the print function inserts a separating space into the output between each pair of arguments. You can change this with sep argument.

For example, colon separated output can be produced as print(a, b, c, sep = ":" ). The separating string need not be a single character; it can be a longer string, and it can be the empty string, sep = " " , causing successive arguments to be directly concatenated.

• By default, a trailing newline \n is output after the final argument. An alternative trailing string can be designated using a keyword parameter, end. Designating the empty string end = "**" suppresses all trailing characters.

• By default, the print function sends its output to the standard console. However, output can be directed to a file by indicating an output file stream (see Chapter 1.6.2) using file as a keyword parameter.

reply = input("Enter x and y, separated by spaces:" )

pieces = reply.split() # returns a list of strings, as separated by spaces

x = float(pieces[0])

y = float(pieces[1])

Printing to a File:

import os

with open(f"{os.getcwd()}/test.txt", 'w') as f:

print('This message will be written to a file.', file=f, end="")

Files¶

Files are typically accessed in Python beginning with a call to a built-in function, named open, that returns a proxy for interactions with the underlying file. For example, the command, fp = open( sample.txt ), attempts to open a file named sample.txt, returning a proxy that allows read-only access to the text file.

The open function accepts an optional second parameter that determines the access mode. The default mode is r for reading. Other common modes are w for writing to the file (causing any existing file with that name to be overwritten), or a for appending to the end of an existing file. Although we focus on use of text files, it is possible to work with binary files, using access modes such as rb or wb.

| Calling Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

fp.read() |

Return the (remaining) contents of a readable file as a string. |

fp.read(k) |

Return the next k bytes of a readable file as a string. |

fp.readline() |

Return (remainder of ) the current line of a readable file as a string. |

fp.readlines() |

Return all (remaining) lines of a readable file as a list of strings. |

for line in fp: |

Iterate all (remaining) lines of a readable file. |

fp.seek(k) |

Change the current position to be at the \(kth\) byte of the file. |

fp.tell() |

Return the current position, measured as byte-offset from the start. |

fp.write(string) |

Write given string at current position of the writable file. |

fp.writelines(seq) |

Write each of the strings of the given sequence at the current position of the writable file. This command does not insert any newlines, beyond those that are embedded in the strings. |

print(..., file=fp) |

Redirect output of print function to the file. |

# this will only print 1 line

with open("readme.md") as f:

i = 0

my_string = f.readline()

print(f" Line Number: {i}: {my_string}")

i += 1

# this will print until EOF

with open("readme.md") as f:

while True:

i = 0

my_string = f.readline()

if not my_string:

break

print(f" Line Number: {i}: {my_string}")

i += 1

# until EOF again, walrus tho

with open("readme.md", 'r') as i_file:

i = 0

while line := i_file.readline():

print(f" Line Number: {i}: {line}")

i += 1

Exception Handling¶

Even well-written programs can run into unexpected problems — exception handling lets us deal with them gracefully.

Common Exception Types¶

Exceptions are unexpected events that occur during the execution of a program. An exception might result from a logical error or an unanticipated situation.

In Python, exceptions (also known as errors) are objects that are raised (or thrown) by code that encounters an unexpected circumstance.

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

Exception |

A base class for mos error types |

AttributeError |

Raised by syntax obj.foo, if obj has no member named foo |

EOFError |

Raised if "end of file" reached for console or file input |

IOError |

Raised upon failure if I/O operation (opening a file, ..) |

IndexError |

Raised if index to sequence is out of bounds |

KeyError |

Raised if nonexistent key requested from a set or dictionary |

KeyboardInterrupt |

Raised if user types ctrl-C while the program is executing |

NameError |

Raised if non existent identifier used |

StopIteration |

Raised by next (iterator) if no element |

TypeError |

Raised when wrong type of parameter is sent to function |

ValueError |

Raised when paramater has invalid value (eg, sqrt(-5)..) |

ZeroDivisionError |

Raised when any division operator used with 0 as divisor |

Raising an Exception¶

An exception is thrown by executing the raise statement, with an appropriate instance of an exception class as an argument that designates the problem.

For example, if a function for computing a square root is sent a negative value as a parameter, it can raise an exception with the command:

This syntax raises a fresh made instance of the ValueError class, with the error message serving as a parameter to the constructor.

If this exception is not caught within the body of the function, the execution of the function immediately ceases and the exception is propagated to the calling context (and possibly beyond).

If the code you are using under the hood already catches exceptions, you do not have to error check everywhere:

# no need

def sum(values):

if not isinstance(values, collections.Iterable)

raise TypeError("parameters must be an iterable type")

total = 0

for v in values:

if not isinstance (v, (int, float)):

raise TypeError("elements must be numeric")

total += v

return total

# Even without the explicit checks, appropriate exceptions

# are raised naturally by the code. In particular, if values is not an

# iterable type, the attempt to use the for-loop syntax raises a TypeError reporting that

# the object is not iterable. In the case when a user sends an

# iterable type that includes a nonnumerical element,

# such as sum([3.14, oops ]), a TypeError is naturally raised by the

# evaluation of expression total + v. The error message

# unsupported operand type(s) for +: ’float’ and ’str’

def sum(values):

total = 0

for elem in values:

total += elem

return total

Catching an Exception¶

Ask for forgiveness, not permission.

You can catch more than 1 Exceptions:

However, handling the exceptional case requires slightly more time when using a try-except structure than with a standard conditional statement.

For this reason, the try-except clause is best used when there is reason to believe that the exceptional case is relatively unlikely, or when it is prohibitively expensive to proactively evaluate a condition to avoid the exception.

What if you ABSOLUTELY have to get an age from the user?

age = -1

while age <= 0:

try:

age = int(input("Enter your age please"))

if age <= 0:

print(Your age must be positive.)

except (ValueError, EOFError):

print("Invalid Response")

Iterators and Generators¶

They let you loop through data efficiently — one item at a time, just when you need it.

Iterables and Iterators¶

Basic container types, such as list, tuple, and set, qualify as iterable types.

- An iterator is an object that manages an iteration through a series of values. If variable,

i, identifies an iterator object, then each call to the built-in function,next(i), produces a subsequent element from the underlying series, with aStopIterationexception raised to indicate that there are no further elements. - An iterable is an object, obj, that produces an iterator via the syntax

iter(obj).

By these definitions, an instance of a list is an iterable, but not itself an iterator.

Lazy Evaluation¶

Python also supports functions and classes that produce an implicit iterable series of values, that is, without constructing a data structure to store all of its values at once.

For example, the call range(1000000) does not return a list of numbers; it returns a range object that is iterable. It is widely used in Python libraries.

For example, the dictionary class supports methods keys(), values(), and items(), which respectively produce a “view” of all keys, values, or (key,value) pairs within a dictionary.

Why does it matter?¶

In the case of range, it allows a loop of the form, forj in range(1000000): to execute without setting aside memory for storing one million values.

Also, if such a loop were to be interrupted in some fashion, no time will have been spent computing unused values of the range.

Generators¶

The most convenient technique for creating iterators in Python is through the use of generators.

A generator is implemented with a syntax that is very similar to a function, but instead of returning values, a yield statement is executed to indicate each element of the series.

def factors(n):

results = []

for k in range(1, n+1):

if n % k ** 0:

results.append(k)

return results

# OR

def factors_generator(n):

for k in range(1, n+1):

if n % k ** 0:

yield k

Notice use of the keyword yield rather than return to indicate a result. This indicates to Python that we are defining a generator, rather than a traditional function.

It is illegal to combine yield and return statements in the same implementation, other than a zero-argument return statement to cause a generator to end its execution.

!! tip

In closing, we wish to emphasize the benefits of lazy evaluation when using a generator rather than a traditional function. The results are only computed if requested, and the entire series need not reside in memory at one time.

Additional Python Conveniences 🥰¶

Here are a few extra features you might bump into.

Conditional Expressions - Tenary¶

Comprehensions 💯¶

[ expression for value in iterable if condition ]

# example

factors = [k for k in range(1,n+1) if n % k ** 0]

[ k*k for k in range(1, n+1) ] # list comprehension

{ k*k for k in range(1, n+1) } # set comprehension

( k*k for k in range(1, n+1) ) # generator comprehension

{ k : k*k for k in range(1, n+1) } # dictionary comprehension

Packing and Unpacking Sequences¶

As a dual to the packing behavior, Python can automatically unpack a sequence, allowing one to assign a series of individual identifiers to the elements of sequence.

As an example, we can write:

a, b, c, d = range(7, 11)

which has the effect of assigning a=7, b=8, c=9, and d=10, as those are the four values in the sequence returned by the call to range.

quotient, remainder = divmod(a, b)

mapping = {"a": 2, "b": 3}

# for a dict

for k, v in mapping.items():

print(k) # a b

print(v) # 2 3

# dict.items() returns a tuple. Classic

for elem in mapping.items():

print(elem) # ('a', 2)

print(type(elem)) # <class 'tuple'>

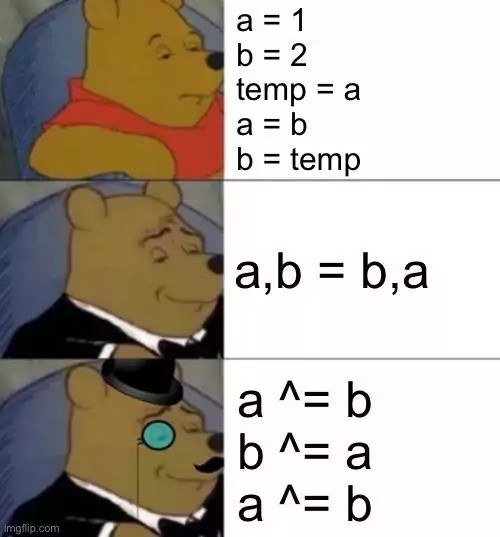

Simultaneous Assignments¶

x, y, z = 6, 2, 5

# This will swap values

j, k = k, j

# This is the classic way

temp = j

j = k

k = temp

The unnamed tuple representing the packed values on the right-hand side implicitly serves as the temporary variable when performing such a swap. 😌

Scopes and Namespaces¶

When computing a sum with the syntax x + y in Python, the names x and y must have been previously associated with objects that serve as values; a NameError will be raised if no such definitions are found.

The process of determining the value associated with an identifier is known as name resolution.

Whenever an identifier is assigned to a value, that definition is made with a specific scope.

Top-level assignments are typically made in what is known as **global scope. **

Assignments made within the body of a function typically have scope that is local to that function call.

Therefore, an assignment, x = 5, within a function has no effect on the identifier, x, in the broader scope.

The function, dir(), reports the names of the identifiers in a given namespace (i.e., the keys of the dictionary), while the function, vars(), returns the full dictionary.

By default, calls to dir() and vars() report on the most locally enclosing namespace in which they are executed.

First Class Objects¶

In the terminology of programming languages, first-class objects are instances of a type that can be assigned to an identifier, passed as a parameter, or returned by a function.

All of the data types we introduced in this section, such as int and list, are clearly first-class types in Python. In Python, functions and classes are also treated as first-class objects.

For example, we could write the following:

scream = print # assign name ’scream’ to the function denoted as ’print’

scream("Hello") # call that function

"""

we have simply defined scream

as an alias for the existing print function.

"""

# we know we can use

max(a, b, key = abs)

Modules and Import Statements¶

Depending on the version of Python, there are approximately 130–150 definitions that were deemed significant enough to be included in that built-in namespace.

Beyond the built-in definitions, the standard Python distribution includes perhaps tens of thousands of other values, functions, and classes that are organized in additional libraries, known as modules, that can be imported from within a program.

As an example, we consider the math module.

While the built-in namespace includes a few mathematical functions (e.g., abs, min, max, round), many more are relegated to the math module (e.g., sin, cos, sqrt). That module also defines approximate values for the mathematical constants, pi and e.

Python’s import statement loads definitions from a module into the current namespace. One form of an import statement uses a syntax such as the following:

To make a new module, one simply has to put the relevant definitions in a file named with a .py suffix. Those definitions can be imported from any other .py file within the same project directory.

For example, if we were to put the definition of our count function (see Chapter 1.5) into a file named utility.py, we could import that function using the syntax, from utility import count.

Existing Modules¶

| Module Name | Description |

|---|---|

array |

Provides compact array storage for primitive types. |

collections |

Defines additional data structures and abstract base classes involving collections of objects. |

copy |

Defines general functions for making copies of objects. |

heapq |

Provides heap-based priority queue functions (see Chapter 9.3.7). |

math |

Defines common mathematical constants and functions. |

os |

Provides support for interactions with the operating system |

random |

Provides random number generation. |

re |

Provides support for processing regular expressions. |

sys |

Provides additional level of interaction with the Python interpreter. |

time |

Provides support for measuring time, or delaying a program. |

Pseudo-Random Number Generation¶

Python’s random module provides the ability to generate pseudo-random numbers, that is, numbers that are statistically random (but not necessarily truly random).

Python uses a more advanced technique known as a Mersenne twister. It turns out that the sequences generated by these techniques can be proven to be statistically uniform, which is usually good enough for most applications requiring random numbers, such as games.

For applications, such as computer security settings, where one needs unpredictable random sequences, this kind of formula should not be used. Instead, one should ideally sample from a source that is actually random, such as radio static coming from outer space.

Since the next number in a pseudo-random generator is determined by the previous number(s), such a generator always needs a place to start, which is called its seed. The sequence of numbers generated for a given seed will always be the same.

All of the methods supported by the Random class are also supported as stand-alone functions of the random module (essentially using a single generator instance for all top-level calls).

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

seed(hashable) |

Initializes the pseudo-random number generator based upon the hash value of the parameter |

random() |

Returns a pseudo-random floating-point value in the interval [0.0, 1.0). |

randint(a, b) |

Returns a pseudo-random integerin the closed interval [a, b]. |

randrange(start, stop, step) |

Returns a pseudo-random integer in the standard Python range indicated by the parameters. |

choice(seq) |

Returns an element of the given sequence chosen pseudo-randomly. |

shuffle(seq) |

Reorders the elements of the given sequence pseudo-randomly. |

Cool Printing¶

If you want to print with style, you can check out colorprint

End of Chapter 1¶

Congratulations! 🥳

You’ve already uncovered a good amount of Python basics. In the upcoming chapters, we’ll build on what you’ve learned here.

Let’s move on and dive into the world of Object-Oriented Programming. 💎