Stacks, Queues and Dequeues 💖¶

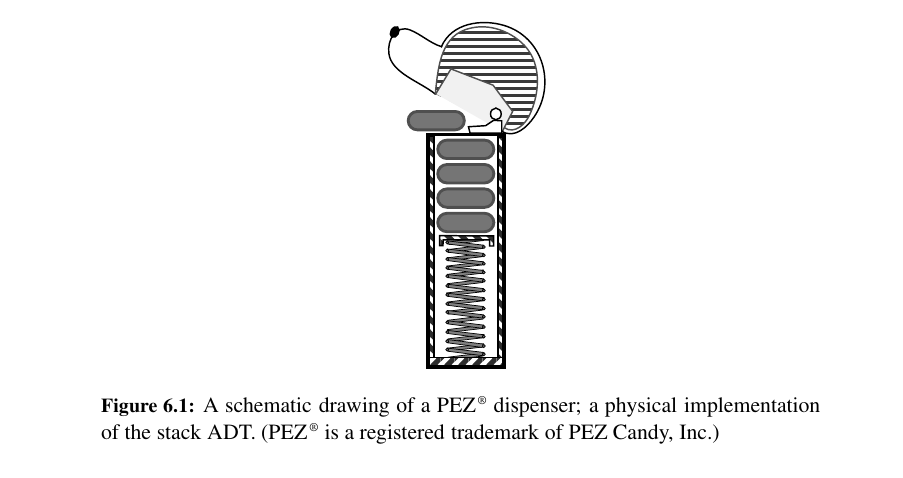

Stacks 💖 💚 💙¶

Stacks are simply just like a pile of clothes. Last in First Out.

A stack is a collection of objects that are inserted and removed according to the last-in, first-out (LIFO) principle.

A user may insert objects into a stack at any time, but may only access or remove the most recently inserted object that remains (at the so-called “top” of the stack).

Internet Web browsers store the addresses of recently visited sites in a stack. Each time a user visits a new site, that site’s address is “pushed” onto the stack of addresses. The browser then allows the user to “pop” back to previously visited sites using the “back” button.

Stacks are used in a host of different applications, and as a tool for many more sophisticated data structures and algorithms. Here are some methods possibly to be used:

| Method | Explained |

|---|---|

s.push(e) |

Add element e to the top of stack S. |

s.pop() |

Remove and return the top element from the stack S, an error occurs if the stack is empty. |

s.top() |

Return a reference to the top element of stack S, without removing it; an error occurs if the stack is empty. |

s.is_empty() |

Return True if stack S does not contain any elements. |

len(s) |

Return the number of elements in stack S; in Python, we implement this with the special method len. |

Simple Array Based Stack Implementation¶

We can implement a stack quite easily by storing its elements in a Python list.

The list class already supports adding an element to the end with the append method, and removing the last element with the pop method, so it is natural to align the top of the stack at the end of the list.

We could just use a list but lists include behaviors that would break the abstraction that a Stack ADT represents.

Adapter Pattern - built stack on top of list.¶

The adapter design pattern applies to any context where we effectively want to modify an existing class so that its methods match those of a related, but different, class or interface.

class Empty(Exception):

pass

class ArrayStack:

"LIFO implementation of a stack using Python lists"

def __init__(self):

"Make a new stack"

self._data = []

def __len__(self):

return len(self._data)

def is_empty(self):

return len(self._data) == 0

def push(self, element):

self._data.append(element)

def top(self):

if self.is_empty():

raise Empty("Stack is empty!")

return self._data[-1]

def pop(self):

"""Remove and return last element of the stack"""

if self.is_empty:

raise Empty("Stack is empty! No items to be popped")

return self._data.pop()

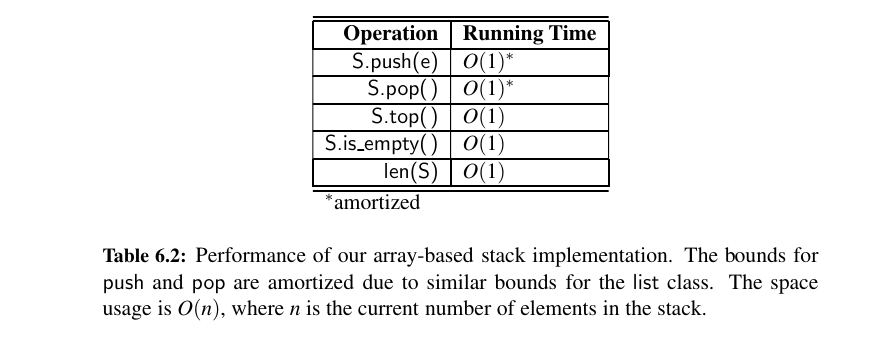

How does the running times look for our ArrayStack ?

Tip

In the analysis of lists, we emphasized that it is more efficient in practice to construct a list with initial length n than it is to start with an empty list and append n items (even though both approaches run in \(O(n)\) time).

So we can avoid amortization by Reserving Capacity.

class ModifiedArrayStackVersionTwo():

"""LIFO implementation of a stack using Python lists

You have to use maxlen to decide the length of the stack

"""

def __init__(self, maxlen = None):

"Make a new stack on max length"

self.maxlen = maxlen

self._data = [None] * self.maxlen

self._size = 0

def __len__(self):

return self._size

def is_empty(self):

return self._size == 0

def push(self, element):

if self.maxlen is not None and self._size == self.maxlen:

raise Full("Stack is full!")

self._data[self._size] = element

self._size += 1

def top(self):

if self.is_empty():

raise Empty("Stack is empty!")

return self._data[self._size -1]

def pop(self):

"""Remove and return last element of the stack"""

if self.is_empty:

raise Empty("Stack is empty! No items to be popped.")

return self._data.pop()

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"A stack with data: {self._data}"

stack1 = ModifiedArrayStackVersionTwo(maxlen = 5)

stack1.push(5)

stack1.push(4)

stack1.push(3)

print(stack1) # A stack with data: [5, 4, 3, None, None]

Reversing Data Using a Stack¶

As a consequence of the LIFO protocol, a stack can be used as a general tool to reverse a data sequence.

Using a list and append for push the code below just works:

def reverse_file(filename):

"""Overwrite given file with its contents line-by-line reversed."""

S = []

original = open(filename)

for line in original:

S.append(line.rstrip("\n"))

# we will re-insert newlines when writing

original.close()

# now we overwrite with contents in LIFO order

output = open(filename, "w")

# reopening file overwrites original

while len(S) != 0:

output.write(S.pop() + "\n" ) # re-insert newline characters

output.close()

reverse_file("sezai.txt")

# Original sezai.txt

# for

# the

# boys

# Processed sezai.txt

# boys

# for

# the

Here is an simpler example:

def reverse_string(string: str) -> str:

stack = []

for elem in string:

stack.append(elem)

result_helper = []

for i in range(len(stack)):

result_helper.append(stack.pop())

return "".join(result_helper)

reverse_string("Wise Oak") # 'kaO esiW'

Matching Parentheses and HTML Tags 😍¶

In this subsection, we explore two related applications of stacks, both of which involve testing for pairs of matching delimiters.

In our first application, we consider arithmetic expressions that may contain various pairs of grouping symbols, such as:

• Parentheses: “(” and “)”

• Braces: “{”and “}”

• Brackets: “[” and “]”

Each opening symbol must match its corresponding closing symbol.

Here is an example using our ArrayStack:

def is_matched(expr):

lefty = '({['

righty = ')}]'

S = ArrayStack()

for c in expr:

if c in lefty:

# each lefty symbol, a symbol is going into stack

S.push(c)

elif c in righty:

# each righty symbol, a symbol is going to be popped

if S.is_empty():

# stack should not be empty right here

return False

if righty.index(c) != lefty.index(S.pop()):

# index of encountered symbol should be equal to

# symbol on top of the stack for lefties

return False

return S.is_empty()

is_matched("fortheboys{asdqwe[ 123 ] asda } ssew () (()) real") # True

Here is the same example using just a list : 💕

def is_matched(expression: str) -> str:

lefty = "({["

righty = ")}]"

stack = []

for c in expression:

if c in lefty:

stack.append(c)

elif c in righty:

if not stack:

return False

elif righty.index(c) != lefty.index(stack.pop()):

return False

return not bool(stack)

is_matched("fortheboys{asdqwe[ 123 ] asda } ssew () (()) real") # True

Each time we encounter an opening symbol, we push that symbol onto S, and each time we encounter a closing symbol, we pop a symbol from the stack S (assuming S is not empty), and check that these two symbols form a valid pair.

Matching Tags in a Markup Language¶

HTML is the standard format for hyperlinked documents on the Internet and XML is an extensible markup language used for a variety of structured data sets.

In an HTML document, portions of text are delimited by HTML tags. A simple opening HTML tag has the form “<name>” and the corresponding closing tag has the form “</name>”.

For example, we see the <body> tag on the first line of Figure 6.3(a), and the matching </body> tag at the close of that document.

Other commonly used HTML tags that are used in this example include:

• body: document body

• h1: section header

• center: center justify

• p: paragraph

• ol: numbered (ordered) list

• li: list item

Ideally, an HTML document should have matching tags, although most browsers tolerate a certain number of mismatching tags.

Here is an example just doing that, using our ArrayStack:

# original

def is_matched_html(raw):

"""Return True if all HTML tags are properly match; False otherwise."""

S = ArrayStack()

j = raw.find('<') # find first '<' character (if any)

while j != -1:

# it has to be the next index, second parameter of str.find()

k = raw.find('>', j+1) # find next '>' character

if k == -1:

return False # invalid tag

tag = raw[j+1:k] # strip away < >

if not tag.startswith('/'): # this is opening tag

S.push(tag)

else: # this is closing tag

if S.is_empty():

return False # nothing to match with

if tag[1:] != S.pop():

return False # mismatched delimiter

# start from somewhere else

j = raw.find('<', k+1) # find next '<' character (if any)

return S.is_empty() # were all opening tags matched?

Here is the same example with just a Python list:

def is_matched_html_(raw: str) -> bool:

stack = []

j = raw.find("<")

while j != -1:

k = raw.find(">", j + 1)

# there has to be a k that is not -1

if k == -1:

return False

# slice to get the tag

tag = raw[j+1:k] # body, center, div .. We basically stripped away the < >

if not tag.startswith("/"): # opening tag

stack.append(tag)

else:

if not stack:

return False

if tag[1:] != stack.pop():

# has to be matching for on top of the stack

return False

# onto the next

j = raw.find("<", k + 1)

return not bool(stack)

raw_html = "<html> <head> <title>The title </title> </head> <body> <p>Example <strong>body</strong> <strong>mind</strong> tag .</p> </body> </html>"

is_matched_html(raw_html) # True

Queues 💕¶

If you are buying a Macbook at Apple Store, you are in a Queue. First in first out.

A queue is a collection of objects that are inserted and removed based on FIFO principle.

Not really feasible to implement with lists.

Here are some methods of queues 🤨:

| Method | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

q.enqueue(e) |

Add element e to the back of queue Q. | |

q.dequeue() |

Remove and return the first element from queue Q an error occurs if the queue is empty. | |

q.first() |

Return a reference to the element at the front of queue Q, without removing it; an error occurs if the queue is empty. | |

q.is_empty() |

Return True if queue Q does not contain any elements. | |

len(q) |

Return the number of elements in queue Q; in Python, we implement this with the special method len . |

Array-Based Queue Implementation 😕¶

For the stack ADT, we created a very simple adapter class that used a Python list as the underlying storage. It may be very tempting to use a similar approach for supporting the queue ADT.

We could enqueue element e by calling append(e) to add it to the end of the list. We could use the syntax pop(0), as opposed to pop(), to intentionally remove the first element from the list when dequeuing.

As easy as this would be to implement, it is ==tragically inefficient==. As we discussed , when pop is called on a list with a non-default index, a loop is executed to shift all elements beyond the specified index to the left, so as to fill the hole in the sequence caused by the pop.

Therefore, a call to pop(0) always causes the worst-case behavior of Θ(n) time.

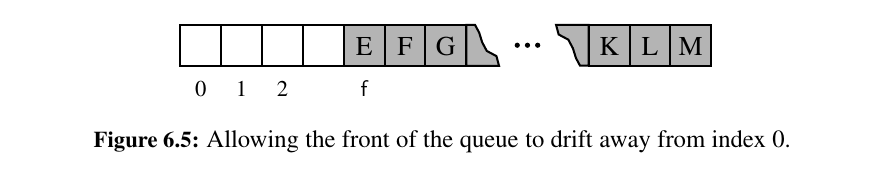

We cannot really set the popped values to None too. Replacing the dequeued entry in the array with a reference to None, and maintain an explicit variable f to store the index of the element that is currently at the front of the queue.

This would result in a huge list in memory especially after long using time of our code. So no bueno.

Using an Array Circularly¶

If we really have to implement the queue with a list and adapter pattern, we can do so with using the list circularly. We will use the modulo operator a lot here.

Here are the protected Members:

| Attribute | Explanation |

|---|---|

_data |

is a reference to a list instance with a fixed capacity. |

_size |

is an integer representing the current number of elements stored in the queue (as opposed to the length of the data list). |

_front |

is an integer that represents the index within data of the first element of the queue (assuming the queue is not empty). |

Enqueuing¶

The goal of the enqueue method is to add a new element to the back of the queue.

We need to determine the proper index at which to place the new element.

Although we do not explicitly maintain an instance variable for the back of the queue, we compute the location of the next opening based on the formula:

Note that we are using the size of the queue as it exists prior to the addition of the new element.

For example, consider a queue with capacity 10, current size 3, and first element at index 5. The three elements of such a queue are stored at indices 5, 6, and 7. The new element should be placed at index (front + size) = 8.

In a case with wrap-around, the use of the modular arithmetic achieves the desired circular semantics.

For example, if our hypothetical queue had 3 elements with the first at index 8, our computation of (8+3)%10 evaluates to 1, which is perfect since the three existing elements occupy indices 8, 9, and 0.

Dequeueing¶

We keep a local reference to the element that will be returned, setting answer = self._data[self._front] just prior to removing the reference to that object from the list, with the assignment self._data[self._front] = None.

The reason for the assignment to None relates to Python’s mechanism for reclaiming unused space.

Internally, Python maintains a count of the number of references that exist to each object. If that count reaches zero, the object is effectively inaccessible, thus the system may reclaim that memory for future use.

We will talk about Memory Management in Chapter 15. 🎉

Resizing the Queue¶

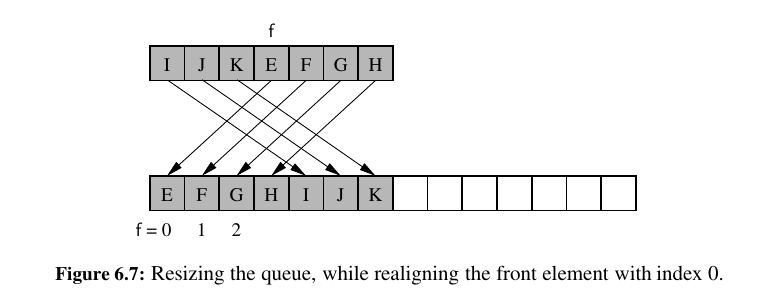

When enqueue is called at a time when the size of the queue equals the size of the underlying list, we rely on a standard technique of doubling the storage capacity of the underlying list.

In this way, our approach is similar to the one used when we implemented a DynamicArray.

After the resizing of the queue, we should fix the index to be at the start of our list. This is different than the implementation in DynamicArray:

Shrinking the Underlying List:¶

A desirable property of a queue implementation is to have its space usage be Θ(n) where n is the current number of elements in the queue. Our ArrayQueue implementation.

It expands the underlying array when enqueue is called with the queue at full capacity, but the dequeue implementation never shrinks the underlying array.

We can implement this strategy by adding these 2 lines in our dequeue method:

Analyzing the Array-Based Queue Implementation (Circular List) 🥰¶

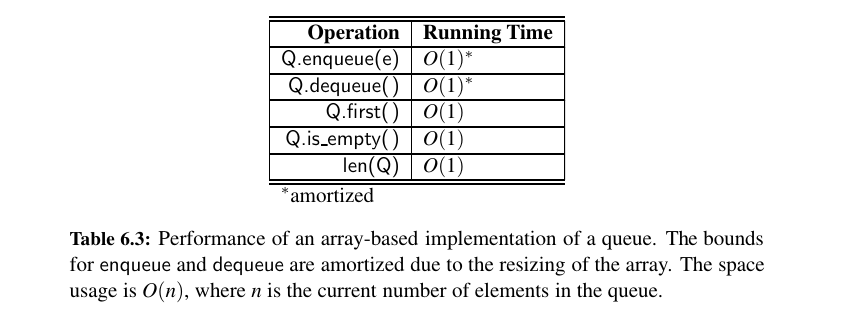

With the exception of the resize utility, all of the methods rely on a constant number of statements involving arithmetic operations, comparisons, and assignments.

Therefore, each method runs in worst-case \(O(1)\) time, except for enqueue and dequeue, which have amortized bounds of \(O(1)\) time

Tip

While we are practicing common data structures while discovering, just know that here are built in Queue's.

queue.Queue and collections.deque serve different purposes. queue.Queue is intended for allowing different threads to communicate using queued messages/data, whereas collections.deque is simply intended as a data structure.

Also, collections.deque is a lot faster. 17 times faster to be precise. Here is a quick benchmark:

import time

from queue import Queue

import collections

q = collections.deque()

t0 = time.time()

for i in range(100000):

q.append(1)

for i in range(100000):

q.popleft()

print ('deque', time.time() - t0) # deque 0.010206222534179688

q_ = Queue(200000)

t0 = time.time()

for i in range(100000):

q_.put(1)

for i in range(100000):

q_.get()

print ('Queue', time.time() - t0) # Queue 0.17466521263122559

So, if you want to use a Queue instead of queue.Queue, use collections.deque. Here is an example:

from collections import deque

q = deque()

# add some items - enqueue

q.append("a")

q.append((12,3))

q.append(4.32)

# dequeue them

q.popleft()

# who is ready to be served?

print(q[0]) # ((12, 3))

# is q empty?

print(f"Queue is empty? {len(q) == 0}")

# or

print(f"is queue non empty? {bool(q)}")

# lenght of the queue at the moment?

print(f"Current length of queue: {len(q)}")

🍎 Double Ended Queues 🍎¶

We next consider a queue-like data structure that supports insertion and deletion at both the front and the back of the queue.

Such a structure is called a double-ended queue, or deque, which is usually pronounced “deck” to avoid confusion with the dequeue method of the regular queue ADT, which is pronounced like the abbreviation “D.Q.”

Unless specified otherwise, the way we use deques is from the collections module.

from collections import deque

q = deque()

q.append(7)

q.appendleft("r")

q.appendleft("c")

print(q) # deque(['c', 'r', 7])

But we will dive deep first and understand how it really works.

For example, we described a restaurant using a queue to maintain a wait list (Who does that anymore?).

Occasionally, the first person might be removed from the queue only to find that a table was not available; typically, the restaurant will re-insert the person at the first position in the queue.

It may also be that a customer at the end of the queue may grow impatient and leave the restaurant. (We will need an even more general data structure if we want to model customers leaving the queue from other positions.)

Here are some expected methods of deque's:

| Method | Explained | |

|---|---|---|

D.add_first(e) |

Add element e to the front of deque D. | |

D.add_last(e) |

Add element e to the back of deque D. | |

D.delete_first() |

Remove and return the first element from deque D; an error occurs if the deque is empty. | |

D.delete_last() |

Remove and return the last element from deque D; an error occurs if the deque is empty. | |

D.first() |

Return (but do not remove) the first element of deque D; an error occurs if the deque is empty. | |

D.last() |

Return (but do not remove) the last element of deque D; an error occurs if the deque is empty. | |

D.is_empty() |

Return True if deque D does not contain any elements. | |

len(D) |

Return the number of elements in deque D; in Python, we implement this with the special method len . |

We can implement the deque ADT in much the same way as the ArrayQueue class. This is given as an exercise in this chapter.

The efficiency of an ArrayDeque is similar to that of an ArrayQueue, with all operations having \(O(1)\) running time, but with that bound being amortized for operations that may change the size of the underlying list.

collections.deque¶

An implementation of a deque class is available in Python’s standard collections module. A summary of the most commonly used behaviors of the collections.deque is down below:

| Our Deque ADT | collections.deque |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

len(D) |

len(D) |

number of elements | |

D.add_first() |

D.appendleft() |

add to beginning | |

D.add_last() |

D.append() |

add to end | |

D.delete_first() |

D.popleft() |

remove from beginning | |

D.delete_last() |

D.pop() |

remove from end | |

D.first() |

D[0] |

access first element | |

D.last() |

D[−1] |

access last element | |

| - | D[j] |

access arbitrary entry by index | |

| - | D[j] = val |

modify arbitrary entry by index | |

| - | D.clear() |

clear all contents | |

| - | D.rotate(k) |

circularly shift rightward k steps | |

| - | D.remove(e) |

remove first matching element | |

| - | D.count(e) |

count number of matches for e |

The collections.deque interface was chosen to be consistent with established naming conventions of Python’s list class, for which append and pop are presumed to act at the end of the list.

Therefore, appendleft and popleft designate an operation at the beginning of the list.

The library deque also mimics a list in that it is an indexed sequence, allowing arbitrary access or modification using the D[j] syntax.

The library deque constructor also supports, optional maxlen parameter to force a fixed-length deque.

However, if a call to append at either end is invoked when the deque is full, it does not throw an error; instead, it causes one element to be dropped from the opposite side.

That is, calling appendleft when the deque is full causes an implicit pop from the ==right side== to make room for the new element.

The current Python distribution implements collections.dequewith a hybrid approach that uses aspects of circular arrays, but organized into blocks that are themselves organized in a doubly linked list (a data structure that we will introduce in the next chapter).

The deque class is formally documented to guarantee \(O(1)\) time operations at either end, but \(O(n)\) time worst-case operations when using index notation near the middle of the deque.

Now, let's move on to Linked Lists, you are doing great! 💚