Object Oriented Programming 😍¶

This chapter is all about object oriented programming.

Goals Principles and Patterns¶

As the name implies, the main “actors” in the object-oriented paradigm are called objects. Each object is an instance of a class.

The class definition typically specifies instance variables, also known as data members, that the object contains, as well as the methods, also known as member functions, that the object can execute.

OOP Design Goals - Why OOP?¶

Why is there such approach in programming?

Robustness, Adaptability and Reusability¶

Software implementations should achieve robustness, adaptability, and reusability.

These are our goals, no matter what kind of application we're building.

1. Robustness (Availability) 🐍¶

We want software to be robust, that is, capable of handling unexpected inputs that are not explicitly defined for its application.

For example, if a program is expecting a positive integer (perhaps representing the price of an item) and instead is given a negative integer, then the program should be able to recover gracefully from this error.

More importantly, in life-critical applications, where a software error can lead to injury or loss of life, software that is not robust could be deadly.

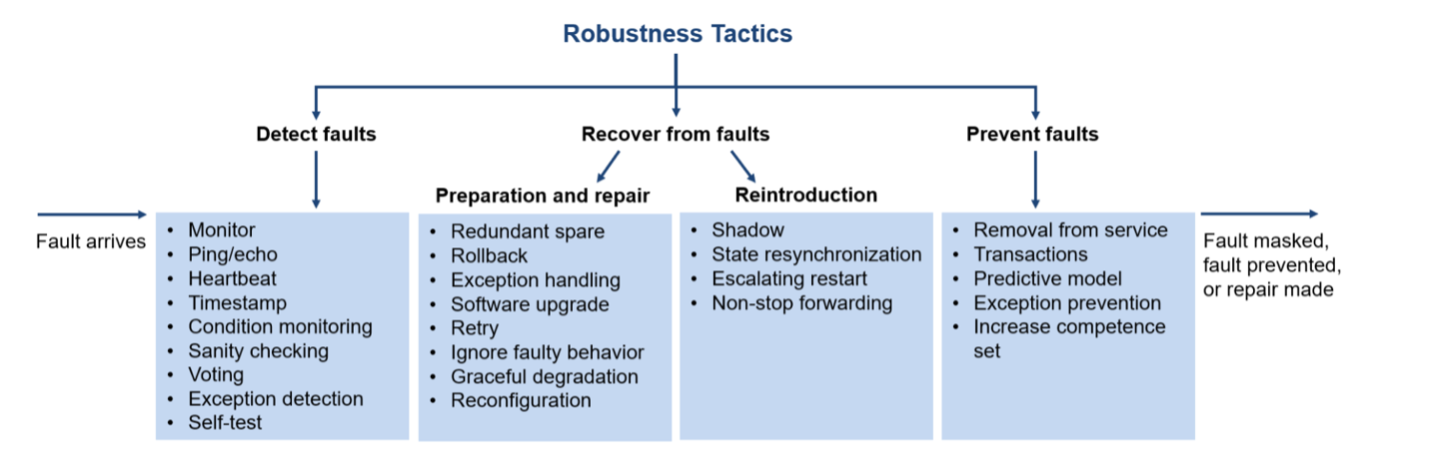

We claim that a system is “robust” if it:

- has acceptable behavior in normal operating conditions over its lifetime

- has acceptable behavior in stressful environmental conditions (e.g., spikes in load).

- can recover from or adapt to states that are outside its proper operating specification

- can evolve and adapt to changes in its environment and stimuli with only minor changes

Here are some tactics for achieving Robustness:

2. Adaptability ♻️¶

Software, needs to be able to evolve over time in response to changing conditions in its environment.

Even if the user-centered design process implemented in a project guarantees a certain degree of user acceptance and yields a richer understanding of the context of use, the completed product's ability to adapt to changing conditions still plays a central role for a broad acceptance.

The operational environment will change, the tasks will be distinct, end-users will be heterogeneous, and their competences and expectations will evolve.

What kind of differences can we expect?

Inter-individual differences¶

Inter-Individual Differences address varieties among several users along manifold dimensions. Physiological characteristics like disabilities are of major concern for application designers if they want to have their system accepted by a large community.

The consideration of user preferences like language, color schemes, modality of interaction, menu options or security properties, and numberless other personal preferences are popular sources of adaptation and can be reused in different applications.

Intra-individual differences¶

Intra-individual differences consider the evolution and further development of a single user, as well as the task over time.

A static system falls short of changing user requirements as the user's activities and goals evolve.

Gotta adapt to your users, use cases, like Airbnb. Do not let your customers be bored.

Environmental differences¶

Environmental Differences basically result from the mobility of computing devices, applications and people, which leads to highly dynamic computing environments.

Unlike desktop applications, which rely on a carefully configured and largely static set of resources, ubiquitous computing applications are subject to changes in available resources such as network connectivity and input/output devices.

It's a challenge to ship for all of these on the right.

They also need to be ready to spontaneously and opportunistically cooperate with previously unknown software services to complete tasks on behalf of users.

Pretty tough job, but also a solid opportunity.

3. Reusability 🏂¶

The same code should be usable as a component of different systems in various applications.

Code reusability is the capacity to re purpose pre-existing code when developing new software applications.

Ideally, code reuse should be easy to implement, and any stable, functional code could freely be reused when building a new software application.

One widely used Python package that you can explore is requests. The requests library is a popular HTTP library for making HTTP requests in Python. It simplifies the process of sending HTTP requests and handling responses.

Simple usage:

import requests

url = 'https://www.example.com'

response = requests.get(url)

if response.status_code ** 200:

print('Request was successful!')

print('Response content:', response.text)

else:

print('Request failed with status code:', response.status_code)

The requests library is highly reusable. 🎉

Object-Oriented Design Principles - Concepts¶

Here are some fundamental concepts about OOP.

1. Modularity¶

Modern software systems typically consist of several different components that must interact correctly in order for the entire system to work properly. Keeping these interactions straight requires that these different components be well organized.

Modularity refers to an organizing principle in which different components of a software system are divided into separate functional units.

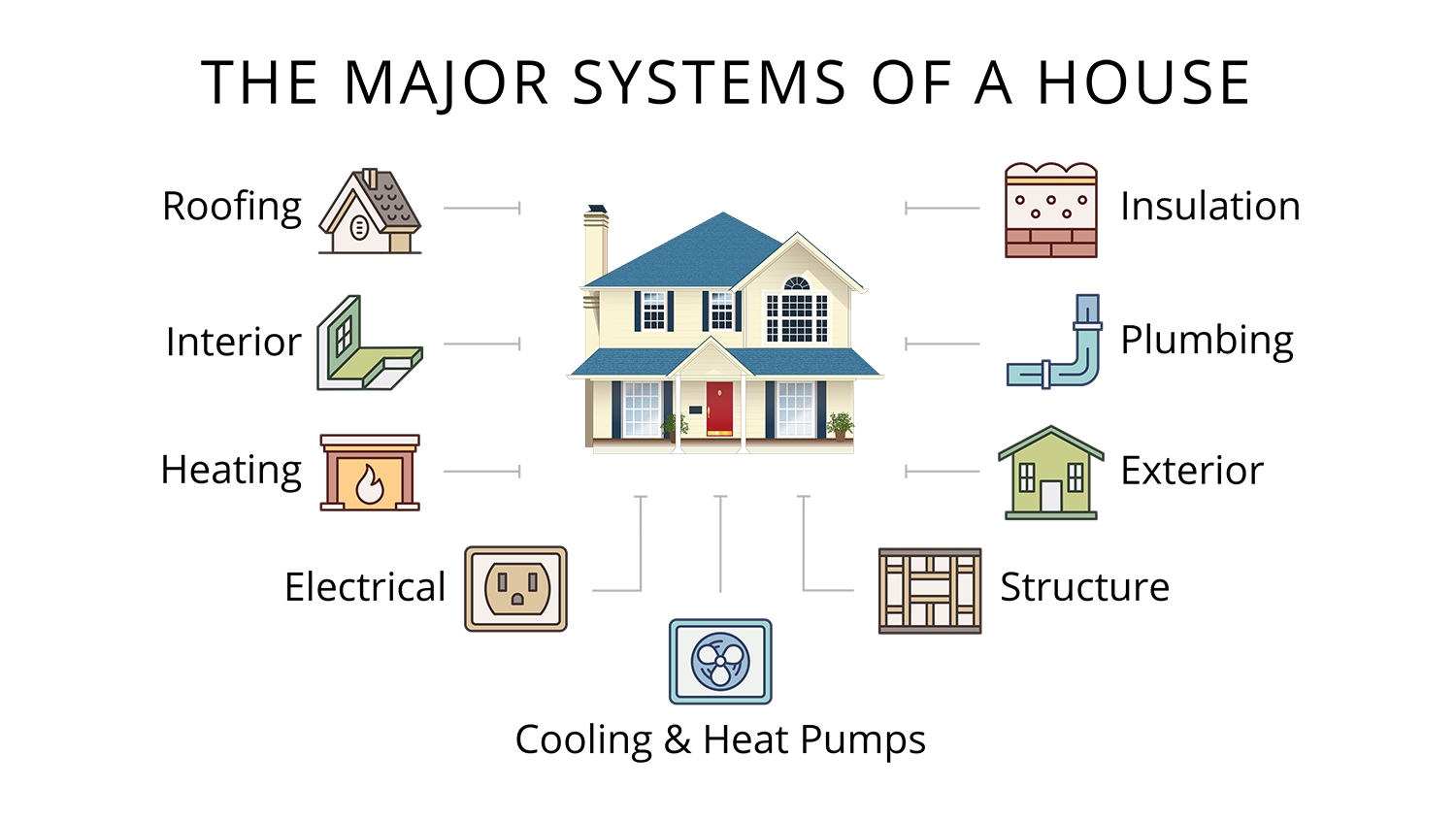

As a real-world analogy, a house or apartment can be viewed as consisting of several interacting units: electrical, heating and cooling, plumbing, and structural.

Rather than viewing these systems as one giant jumble of wires, vents, pipes, and boards, the organized architect designing a house or apartment will view them as separate modules that interact in well-defined ways.

In so doing, he or she is using modularity to bring a clarity of thought that provides a natural way of organizing functions into distinct manageable units.

Modularity helps everything.

Robustness is greatly increased because it is easier to test and debug separate components before they are integrated into a larger software system.

2. Abstraction¶

The notion of abstraction is to distill ( to distill something said or written is to reduce it but keep the most important part) a complicated system down to its most fundamental parts.

Typically, describing the parts of a system involves naming them and explaining their functionality. Applying the abstraction paradigm to the design of data structures gives rise to abstract data types (ADTs).

An ADT is a mathematical model of a data structure that specifies the type of data stored, the operations supported on them, and the types of parameters of the operations.

An ADT specifies what each operation does, but not how it does it. We will typically refer to the collective set of behaviors supported by an ADT as its public interface.

Tip

As a programming language, Python provides a great deal of latitude in regard to the specification of an interface. Python has a tradition of treating abstractions implicitly using a mechanism known as duck typing.

As a interpreted and dynamically typed language, there is no “compile time” checking of data types in Python, and no formal requirement for declarations of abstract base classes. Instead programmers assume that an object supports a set of known behaviors, with the interpreter raising a run-time error if those assumptions fail.

The description of this as “duck typing” comes from an adage attributed to poet James Whitcomb Riley, stating that “when I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.”

Here are some examples of Duck Typing functionality:

Imagine I have a magic wand. It has special powers. If I wave the wand and say "Drive!" to a car, well then, it drives!

Does it work on other things? Not sure: so I try it on a truck. Wow - it drives too! I then try it on planes, trains and 1 Woods (they are a type of golf club which people use to 'drive' a golf ball). They all drive!

But would it work on say, a teacup? Error: Poof! That didn't work out so good. Teacups can't drive, duh!?

This is basically the concept of duck typing. It's a try-before-you-buy system. If it works, all is well. But if it fails, like a grenade still in your hand.

In other words, we are interested in what the object can do, rather than with what the object is.

This determines whether an object can be used for a particular purpose. An object's suitability is determined by the presence of certain attributes, rather than by the type of the object itself.

More formally, Python supports abstract data types using a mechanism known as an abstract base class (ABC). An abstract base class cannot be instantiated (i.e., you cannot directly create an instance of that class), but it defines one or more common methods that all implementations of the abstraction must have.

We will make use of several existing abstract base classes coming from Python’s collections module, which includes definitions for several common data structure ADTs, and concrete implementations of some of those abstractions.

3. Encapsulation¶

Different components of a software system should not reveal the internal details of their respective implementations.

One of the main advantages of encapsulation is that it gives one programmer freedom to implement the details of a component, without concern that other programmers will be writing code that intricately depends on those internal decisions.

The only constraint on the programmer of a component is to maintain the public interface for the component, as other programmers will be writing code that depends on that interface.

Encapsulation yields robustness and adaptability, for it allows the implementation details of parts of a program to change without adversely affecting other parts, thereby making it easier to fix bugs or add new functionality with relatively local changes to a component.

- Encapsulation is the bundling of data (attributes) and methods that operate on the data into a single unit (class).

- It restricts direct access to some of the object's components and can prevent unintended interference.

- Example: Accessing the

nameattribute through a method (get_name) in theAnimalclass.

class Animal:

# ... (previous code)

def get_name(self):

return self.name

lion = Animal("Leo", 5)

print(lion.get_name()) # Output: Leo`

Python provides only loose support for encapsulation.

By convention, names of members of a class (both data members and member functions) that start with a single underscore _ character (e.g., _secret) are assumed to be nonpublic and should not be relied upon. Those conventions are reinforced by the intentional omission of those members from automatically generated documentation.

In Python, we have @property decorator for getters and setters. Here is an example:

# Python program to illustrate the use of

# @property decorator

class Celsius:

# Defining init method with its parameter

def __init__(self, temp = 0):

self._temperature = temp

# @property decorator

# This method serves as a getter for the `_temp` attribute.

@property

def temp(self):

"""Getter method for temperature"""

# Prints the assigned temperature value

print("The value of the temperature is: ")

return self._temperature

# Setter method

@temp.setter

def temp(self, val):

# If temperature is less than -273 than a value

# error is thrown

if val < -273:

raise ValueError("It is a value error.")

# Prints this if the value of the temperature is set

print("The value of the temperature is set.")

self._temperature = val

# Creating object for the stated class

cel = Celsius()

# Setting the temperature value

cel.temp = -270

# Prints the temperature that is set

print(cel.temp)

# Setting the temperature value to -300

# which is not possible so, an error is

# thrown

cel.temp = -300

print(cel.temp)

4.Inheritance:¶

Inheritance allows a class (subclass or derived class) to inherit the properties and behaviors of another class (super class or base class).

It promotes code reusability.

Example: Making a Lion class that inherits from the Animal class. 🐯

class Lion(Animal):

def roar(self):

print("Roar!")

simba = Lion("Simba", 3)

simba.eat() # Output: Simba is eating.

simba.roar() # Output: Roar!

5. Polymorphism:¶

Polymorphism allows objects of different classes to be treated as objects of a common base class.

It enables flexibility and allows a single interface to represent different types.

Compile-Time Polymorphism (Static Binding):

- Achieved through method overloading and operator overloading.

- Involves multiple methods or operators with the same name but different parameter types or numbers of parameters.

- The appropriate method or operator is selected during compile time based on the types of arguments.

"""

This does not work. The interpreter will use the latest definition of the function.

"""

def add(x, y):

return x + y

def add(x, y, z):

return x + y + z

But this will work:

Run-Time Polymorphism (Dynamic Binding):

- Achieved through method overriding (also known as dynamic polymorphism).

- Involves a base class and a derived class, where the derived class provides a specific implementation for a method that is already defined in the base class.

- The decision on which method to execute is made at runtime based on the actual type of the object.

class Animal:

def make_sound(self):

print("Generic animal sound.")

class Cat(Animal):

def make_sound(self):

print("Meow!")

def animal_sound(animal):

animal.make_sound()

cat = Cat()

animal_sound(cat) # Output: Meow!

Function Overriding:¶

Function overriding is a specific form of polymorphism that occurs when a derived class provides a specific implementation for a method that is already defined in its base class.

It allows objects of the derived class to be treated as objects of the base class while executing their own specific implementations.

Design Patterns¶

Computing researchers and practitioners have developed a variety of organizational concepts and methodologies for designing quality object-oriented software that is concise, correct, and reusable.

The algorithm design patterns we discuss include the following:

- Recursion (Chapter 4)

- Amortization (Chapter 5.3 and 11.4)

- Divide-and-conquer (Chapter 12.2.1)

- Prune-and-search, also known as decrease-and-conquer (Chapter 12.7.1)

- Brute force (Chapter 13.2.1)

- Dynamic programming (Chapter 13.3).

- The greedy method (Chapter 13.4.2, 14.6.2, and 14.7)

Software engineering design patterns we discuss include:

- Iterator (Chapter 1.8 and 2.3.4)

- Adapter (Chapter 6.1.2)

- Position (Chapter 7.4 and 8.1.2)

- Composition (Chapter 7.6.1, 9.2.1, and 10.1.4)

- Template method (Chapter 2.4.3, 8.4.6, 10.1.3, 10.5.2, and 11.2.1)

- Locator (Chapter 9.5.1)

- Factory method (Chapter 11.2.1)

Rather than explain each of these concepts here, however, we introduce them throughout the text as noted above. 🥳

Software Development¶

The design step is perhaps the most important phase in the process of developing software.

“Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Steve Jobs.¶

How should we do it?

-

Responsibilities: Divide the work into different actors, each with a different responsibility. Try to describe responsibilities using action verbs. These actors will form the classes for the program.

-

Independence: Define the work for each class to be as independent from other classes as possible. Subdivide responsibilities between classes so that each class has autonomy over some aspect of the program. Give data (as instance variables) to the class that has jurisdiction over the actions that require access to this data.

-

Behaviors: Define the behaviors for each class carefully and precisely, so that the consequences of each action performed by a class will be well understood by other classes that interact with it. These behaviors will define the methods that this class performs, and the set of behaviors for a class are the interface to the class, as these form the means for other pieces of code to interact with objects from the class.

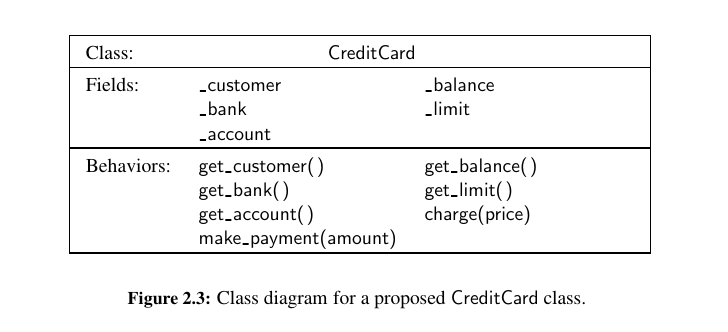

Defining the classes, together with their instance variables and methods, are key to the design of an object-oriented program.

A good programmer will naturally develop greater skill in performing these tasks over time, as experience teaches him or her to notice patterns in the requirements of a program that match patterns that he or she has seen before.

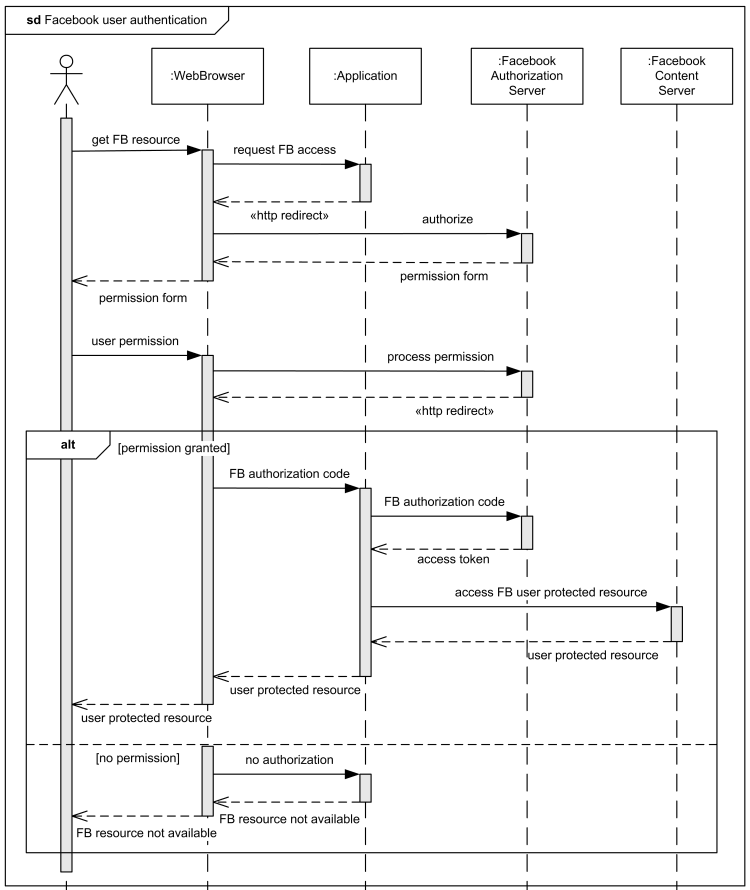

As the design takes form, a standard approach to explain and document the design is the use of UML (Unified Modeling Language) diagrams to express the organization of a program. UML diagrams are a standard visual notation to express object-oriented software designs.

There are class diagrams, deployment diagrams, activity and sequence diagrams. You can check them out here.

UML 2.5 Structure Diagrams¶

Structure diagrams show static structure of the system and its parts on different abstraction and implementation levels and how those parts are related to each other. The elements in a structure diagram represent the meaningful concepts of a system, and may include abstract, real world and implementation concepts.

A class diagram is down below:

UML 2.5 Behavior Diagrams¶

Behavior diagrams show the dynamic behavior of the objects in a system, which can be described as a series of changes to the system over time.

A sequence diagram is given down below:

Pseudo-Code¶

Pseudo-code is not a computer program, but is more structured than usual prose. It is a mixture of natural language and high-level programming constructs that describe the main ideas behind a generic implementation of a data structure or algorithm.

Coding Style and Documentation 👨💻¶

Programs should be made easy to read and understand. Whether you are coding with humans or LLMs.

Documentation¶

Python provides integrated support for embedding formal documentation directly in source code using a mechanism known as a docstring.

Guidelines for authoring useful docstrings are available at: PEP257. I use Google's guide

Testing and Debugging¶

Testing is the process of experimentally checking the correctness of a program, while debugging is the process of tracking the execution of a program and discovering the errors in it. Testing and debugging are often the most time-consuming activity in the development of a program.

At the very minimum, we should make sure that every method of a class is tested at least once (method coverage).

Even better, each code statement in the program should be executed at least once (statement coverage).

Programs often tend to fail on special cases of the input. Such cases need to be carefully identified and tested.

For example, when testing a method that sorts (that is, puts in order) a sequence of integers, we should consider the following inputs:

- The sequence has zero length (no elements).

- The sequence has one element.

- All the elements of the sequence are the same.

- The sequence is already sorted.

- The sequence is reverse sorted.

As software is maintained, the act of regression testing is used, whereby all previous tests are re-executed to ensure that changes to the software do not introduce new bugs in previously tested components.

Bottom-up testing proceeds from lower-level components to higher-level components.

For example, bottom-level functions, which do not invoke other functions, are tested first, followed by functions that call only bottom-level functions, and soon.

Similarly a class that does not depend upon any other classes can be tested before another class that depends on the former. This form of testing is usually described as unit testing, as the functionality of a specific component is tested in isolation of the larger software project.

Debugging¶

The simplest debugging technique consists of using print()statements to track the values of variables during the execution of the program.

A better approach is to run the program within a debugger, which is a specialized environment for controlling and monitoring the execution of a program.

The basic functionality provided by a debugger is the insertion of breakpoints within the code. When the program is executed within the debugger, it stops at each breakpoint. While the program is stopped, the current value of variables can be inspected.

The standard Python distribution includes a module named pdb, which provides debugging support directly within the interpreter.

Class Definitions¶

A class serves as the primary means for abstraction in object-oriented programming.

In Python, every piece of data is represented as an instance of some class.

A class provides a set of behaviors in the form of member functions (also known as methods), with implementations that are common to all instances of that class.

A class also serves as a blueprint for its instances, effectively determining the way that state information for each instance is represented in the form of attributes (also known as fields, instance variables, or data members).

Syntactically, self identifies the instance upon which a method is invoked. This is not required, it is just a tradition and you want your Python code to be looking like Python code for other developers.

The Constructor¶

Internally, object making in Python first involves a call to the special __new__ method, which is the actual constructor.

However, in most cases, we don't override __new__. Instead, we customize initialization behavior using the __init__ method — the initializer — which sets up the internal state of a newly created CreditCard object by assigning values to its instance variables.

Internally, this results in a call to the specially named __init__ method that serves as the constructor of the class.

It's primary responsibility is to establish the state of a newly made CreditCard object with appropriate instance variables.

Encapsulation in Class¶

A single leading underscore in the name of a data member, such as _balance, implies that it is intended as nonpublic. Users of a class should not directly access such members.

As a general rule, we will treat all data members as nonpublic. This allows us to better enforce a consistent state for all instances.

We can provide accessors, such as get_balance, to provide a user of our class read-only access to a trait. If we wish to allow the user to change the state, we can provide appropriate update methods.

In the context of data structures, encapsulating the internal representation allows us greater flexibility to redesign the way a class works, perhaps to improve the efficiency of the structure.

Error Checking in Classes¶

If a user were to make a call such as visa.charge("candy"), our code would presumably crash when attempting to add that parameter to the current balance.

If this class were to be widely used in a library, we might use more rigorous techniques to raise a TypeError when facing such misuse (see Exception Handling)

Beyond the obvious type errors, our implementation may be susceptible to logical errors.

For example, if a user were allowed to charge a negative price, such as visa.charge(−300), that would serve to lower the customer’s balance. This provides a loophole for lowering a balance without making a payment.

Testing the Class - Method and Statement Coverage¶

We start by getting to method coverage first, meaning every method in the class is at least tested once.

After that, there should be a statement coverage, meaning each code statement in the program should be executed at least once.

We can literally put some code in main an look if all the methods are acting accordingly.

if __name__ == "__main__":

wallet = []

wallet.append(CreditCard( "John Bowman" , "California Savings" ,

"5391 0375 9387 5309" , 2500) )

wallet.append(CreditCard( "John Bowman" , "California Federal" ,

"3485 0399 3395 1954 ", 3500) )

wallet.append(CreditCard( "John Bowman" , "California Finance" ,

"5391 0375 9387 5309" , 5000) )

for val in range(1, 17):

wallet[0].charge(val)

wallet[1].charge(2*val)

wallet[2].charge(3*val)

for c in range(3):

print( "Customer =" , wallet[c].get_customer())

print( "Bank =" , wallet[c].get_bank())

print( "Account =" , wallet[c].get_account())

print( "Limit = ", wallet[c].get_limit())

print( "Balance =" , wallet[c].get_balance())

while wallet[c].get_balance( ) > 100:

wallet[c].make_payment(100)

print( "New balance =" , wallet[c].get_balance( ))

print()

OR - we can write Unit tests to check all of them automatically. 🥳

Operator Overloading and Python’s Special Methods¶

By default, the + operator is undefined for a new class. However, the author of a class may provide a definition using a technique known as operator overloading.

This is done by implementing a specially named method. In particular, the + operator is overloaded by implementing a method named __add__ , which takes the right-hand operand as a parameter and which returns the result of the expression.

That is, the syntax, a + b, is converted to a method call on object a of the form, `a.add(b).

Non-Operator Overloads¶

For example, the syntax, str(foo), is formally a call to the constructor for the string class.

The conversion to a Boolean value is particularly important, because the syntax, if foo:, can be used even when foo is not formally a Boolean value (see Chapter 1.4.1).

For a user-defined class, that condition is evaluated by the special method foo.__bool__().

All overloaded operations down below:

| Common Syntax | Special Method Form |

|---|---|

a + b |

a.__add__(b) alternatively b.__radd__(a) |

a − b |

a.__sub__(b) alternatively b.__rsub__ (a) |

a * b |

a.__mul__(b) alternatively b.__rmul__(a) |

a / b |

a.__truediv__(b) alternatively b.__rtruediv__(a) |

a // b |

a.__floordiv__(b) alternatively b.__rfloordiv__(a) |

a % b |

a.__mod__(b) alternatively b.__rmod__(a) |

a ** b |

a.__pow (b) alternatively b.__rpow__(a) |

a << b |

a.__lshift__(b) alternatively b.__rlshift__(a) |

a >> b |

a.__rshift__(b) alternatively b.__rrshift__(a) |

a & b |

a.__and__(b) alternatively b.__rand__(a) |

a ˆ b |

a.__xor__(b) alternatively b.__rxor__(a) |

a \| b |

a.__or__(b) alternatively b.__ror__(a) |

a += b |

a.__iadd__(b) |

a −= b |

a.__isub__(b) |

a *= b |

a.__imul__(b) |

| ... | ... |

+a |

a.__pos__( ) |

−a |

a.__neg__( ) |

~ a |

a.__invert__( ) |

abs(a) |

a.__abs__( ) |

a < b |

a.__lt__(b) |

a <= b |

a.__le__(b) |

a > b |

a.__gt__(b) |

a >= b |

a.__ge__(b) |

a == b |

a.__eq__(b) |

a != b |

a.__ne__(b) |

v in a |

a.__contains__(v) |

a[k] |

a.__getitem__(k) |

a[k] = v |

a.__setitem__(k,v) |

del a[k] |

a.__delitem__(k) |

a(arg1, arg2, ...) |

a.__call__(arg1, arg2, ...) |

len(a) |

a.__len__() |

hash(a) |

a.__hash__() |

iter(a) |

a.__iter__() |

next(a) |

a.__next__() |

bool(a) |

a.__bool__() |

float(a) |

a.__float__() |

int(a) |

a.__int__() |

repr(a) |

a.__repr__() |

reversed(a) |

a.__reversed__() |

str(a) |

a.__str__() |

Tip

About __add__ vs __radd__:

Python calls __radd__ only when the object on the right side of the + is your class instance, but the object on the left is not an instance of your class. Source

The __add__ method for the object on the left is called instead in all other cases:

class Forest:

def __init__(self, name, location, age):

self.age = age

self.name = name

self.location = location

def __add__(self, other_tree):

if isinstance(other_tree, (int, tuple)):

return Forest(self.name, self.location, self.age + other_tree)

else:

return Forest(self.name + "_" + other_tree.name, self.location,

self.age if self.age > other_tree.age else other_tree.age)

def __radd__(self, getting_older):

return Forest(self.name , self.location ,

self.age + getting_older if isinstance(getting_older, (int, float)) else self.age)

def __repr__(self):

return f"""A forest called: {self.name}, at location: {self.location}, with age: {self.age}"""

for1 = Forest("north", "USA", 23)

for2 = Forest("south", "NET", 25)

# this uses add

print(for1 + for2)

# A forest called: north_south, at location: TUR, with age: 25

# this uses add

print(for1 + 5)

# A forest called: north, at location: TUR, with age: 28

# this uses radd

print(12 + for1)

# A forest called: north, at location: TUR, with age: 35

Implied Methods¶

As a general rule, if a particular special method is not implemented in a user-defined class, the standard syntax that relies upon that method will raise an exception. For example, evaluating the expression, a + b, for instances of a user-defined class without __add__ or __radd__ will raise an error. 😮

There are some operators that have default definitions provided by Python, in the absence of special methods, and there are some operators whose definitions are derived from others.

For example, the bool method, which supports the syntax if foo:, has default semantics so that every object other than None is evaluated as True.

However, for container types, the len method is typically defined to return the size of the container.

If such a method exists, then the evaluation of bool(foo) is interpreted by default to be True for instances with nonzero length, and False for instances with zero length, allowing a syntax such as if waitlist: to be used to test whether there are one or more entries in the wait list.

Warning

We should be careful that some natural implications are not automatically provided by Python.

For example, the __eq__ method supports syntax a == b, but providing that method does not affect the evaluation of syntax a != b. (The __ne__ method should be provided, typically returning not (a == b) as a result.)

Similarly, providing a __lt__ method supports syntax a < b, and indirectly b > a, but providing both __lt__ and __eq__ does not imply semantics for a <= b 😎

To demonstrate the use of operator overloading we give 2 examples here:

class Vector:

"""Represent a vector in multidimensional space"""

def __init__(self, d) :

"""Make a d-dimensional vector of zeros"""

self._coords = [0] * d

def __len__(self):

"""Return the dimension of the vector"""

return len(self._coords)

def __getitem__(self, j):

"""Return jth coordinate of the vector"""

return self._coords[j]

def __setitem__(self, j, val):

"""Set jth coordinate of vector to given value val."""

self._coords[j] = val

def __add__(self, other):

"""Return sum of 2 vectors"""

if len(self) != len(other):

raise ValueError("dimensions must match, in order to add two vectors")

result = Vector(len(self))

for j in range(len(self)):

result[j] = self[j] + other[j]

return result

def __eq__(self, other):

"""Return True if vector has same coordinates as other"""

if not isinstance(other, Vector):

raise TypeError("Cannot compare a Vector with something other than a Vector")

return self._coords == other._coords

def __ne__(self, other):

"""Return True is two vectors differ"""

return not self == other

def __str__(self):

"""String representation of the vector"""

return f"< {str(self._coords)[1:-1]} >"

Iterators 💛¶

Iterators support __next__ which returns the next element of the collection if any, or raises StopIteration exception to indicate that there are no further elements.

We generally implement generators.

Python helps by providing automatic iterator implementation for any class that defines both __len__ and __getitem__. Here is an example.

class SequenceIterator:

"""An iterator for any of Python's sequence types"""

def __init__(self, sequence):

"""Makes an iterator for any given sequence"""

self._seq = sequence # keep a reference for the underlying data

self._k = -1 # will increment to 0 for the first call of next

def __next__(self):

"""Return the next element, or else raise StopIteration error"""

self._k += 1

if self._k < len(self._seq):

return(self._seq[self._k])

else:

raise StopIteration

def __iter__(self):

"""By convention, an iterator must return itself as an iterator"""

return self

my_listt = [1,3,4445,51234]

my_iterator = SequenceIterator(my_listt)

print(next(my_iterator)) # 1

print(next(my_iterator)) # 3

print(next(my_iterator)) # 4445

print(next(my_iterator)) # 51234

print(next(my_iterator)) # StopIteration

Prior to Python 3, range was a function. It returned huge lists. 😮 This was unnecessarily expensive for time and memory usage.

This is solved by lazy evaluation.

Rather than creating a new list instance, range is a class that can effectively represent the desired range of elements without ever storing them explicitly in memory.

An the other example, Range:

class Range:

"""A class that mimics the built in range class"""

def __init__(self, start, stop = None, step = 1):

"""Initialize a Range Instance.

Semantics similar to built in Range class

"""

if step == 0:

raise ValueError("step cannot be 0")

if stop is None: # special case of range(n)

start, stop = 0, start # should be treated as if range(0, n)

# calculate the effective length once

self._length = max(0, (stop - start + step - 1) // step)

# need knowladge of start and step (but not stop) to support __getitem__

self._start = start

self._step = step

def __len__(self):

"""return the number of entries in that range"""

return self._length

def __getitem__(self, k):

"""return entry at index k (using stantard interpretation if negative)"""

if k < 0:

k += len(self)

if not 0 <= k < self._length:

raise IndexError("Index out of range")

return self._start + k * self._step

def __repr__(self):

return f"A Range with {self._length} elements starting from" + \

f" {self._start} with {self._step} as step size"

range1 = Range(8)

range2 = Range(0,10)

range3 = Range(0,10, 3)

print(range1) # A Range with 8 elements starting from 0 with 1 as step size

print(range2) # A Range with 10 elements starting from 0 with 1 as step size

print(range3) # A Range with 4 elements starting from 0 with 3 as step size

Inheritance¶

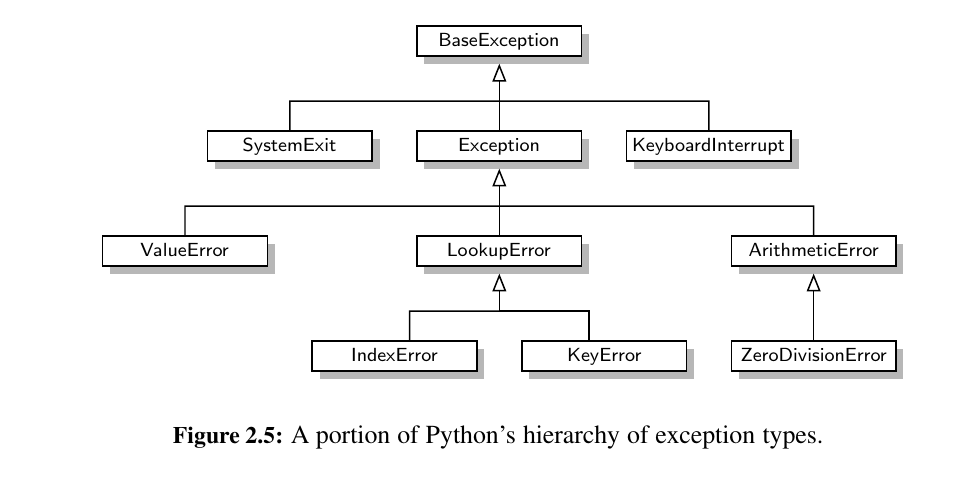

A natural way to organize various structural components of a software package is in a hierarchical fashion:

In object-oriented programming, the mechanism for a modular and hierarchical organization is a technique known as inheritance.

In object-oriented terminology, the existing class is typically described as the base class, parent class, or super-class, while the newly defined class is known as the subclass or child class.

There are two ways in which a subclass can differentiate itself from its super-class.

A subclass may specialize an existing behavior by providing a new implementation that overrides an existing method. A subclass may also extend its super-class by providing brand new methods.

Here is an example of a Extended class.

The body of our new constructor relies upon making a call to the inherited constructor to perform most of the initialization (in fact, everything other than the recording of the percentage rate).

The mechanism for calling the inherited constructor relies on the syntax, super():

- The

process_monthmethod is a new behavior, so there is no inherited version upon which to rely. - Several object-oriented languages (e.g., Java, C++) draw a distinction for nonpublic members, allowing declarations of protected or private access modes. Members that are declared as protected are accessible to subclasses, but not to the general public, while members that are declared as private are not accessible to either.

- In this respect, we are using

_balanceas if it were protected (but not private). - Python does not support formal access control, but names beginning with a single underscore

_are conventionally similar to protected, while names beginning with a double underscore__(other than special methods) are similar to private.

class Members:

def __init__(self, a, b, c):

# this is a similar to public member

self.a = a

# this is a similar to protected member

self._b = b

# this is similar to private member

self.__c = c

mem = Members(1,2,3)

print(mem.a) # 1

print(mem._b) # 2

print(mem.__c) # AttributeError: 'Members' object has no attribute '__c'

print(mem._Members__c) # 3

Here is an another example of inheritance based on some iterators

| progressions.py | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 | |

Abstract Base Classes¶

The real purpose of the Progression class was to centralize the implementations of behaviors that other progressions needed, thereby streamlining the code that is relegated to those subclasses.

In classic object-oriented terminology, we say a class is an abstract base class if its only purpose is to serve as a base class through inheritance.

More formally, an abstract base class is one that cannot be directly instantiated, while a concrete class is one that can be instantiated. By this definition, our Progression class is technically concrete, although we essentially designed it as an abstract base class. 🥰

In statically typed languages such as Java and C++, an abstract base class serves as a formal type that may guarantee one or more abstract methods. This provides support for polymorphism, as a variable may have an abstract base class as its declared type, even though it refers to an instance of a concrete subclass.

Because there are no declared types in Python, this kind of polymorphism can be accomplished without the need for a unifying abstract base class. For this reason, there is not as strong a tradition of defining abstract base classes in Python, although Python’s abc module provides support for defining a formal abstract base class.

Our reason for focusing on abstract base classes in our study of data structures is that Python’s collections module provides several abstract base classes that assist when defining custom data structures that share a common interface with some of Python’s built-in data structures.

These rely on an object-oriented software design pattern known as the template method pattern.

The template method pattern is when an abstract base class provides concrete behaviors that rely upon calls to other abstract behaviors. In that way, as soon as a subclass provides definitions for the missing abstract behaviors, the inherited concrete behaviors are well defined.

Here is an abstract base class similar to collections.Sequence:

This implementation relies on two advanced Python techniques.

The first is that we declare the ABCMeta class of the abc module as a metaclass of our Sequence

class.

A metaclass is different from a superclass, in that it provides a template for the class definition itself. Specifically, the ABCMeta declaration assures that the constructor for the class raises an error.

The second advanced technique is the use of the @abstractmethod decorator immediately before the __len__ and __getitem__ methods are declared. That declares these two particular methods to be abstract, meaning that we do not provide an implementation within our Sequence base class, but that we expect any concrete subclasses to support those two methods.

Namespaces and Object Orientation¶

A namespace is an abstraction that manages all of the identifiers that are defined in a particular scope, mapping each name to its associated value.

In Python, functions, classes, and modules are all first-class objects, and so the “value” associated with an identifier in a namespace may in fact be a function, class, or module.

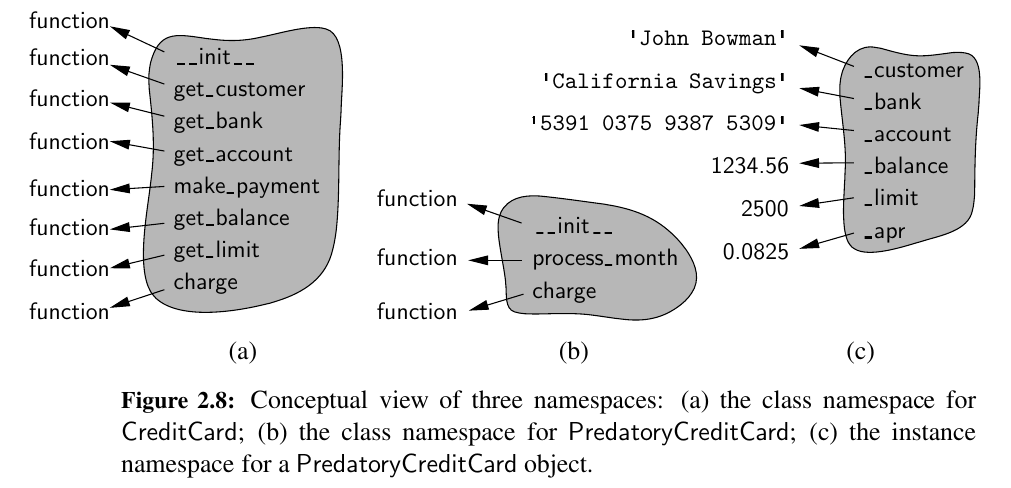

Instance and Class Namespaces¶

Instance namespace, manages attributes specific to an individual object.

Each CreditCard object has balance, account number, limit and card number.

Class Namespaces are defined for each class.

For example, the make_payment method of the CreditCard class from Class Definitions is not stored independently by each instance of that class.

The CreditCard class namespace includes : __init__ , get_customer, get_bank, get_account, get_balance, get_limit, charge and make_payment.

Extra about Namespaces:¶

Here is the source for it.

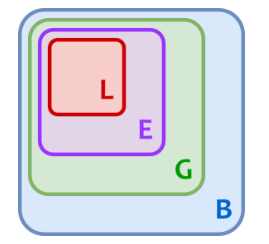

In a Python program, there are four types of namespaces:

- Built-In

- Global

- Enclosing

- Local

Built in Namespace¶

The built in namespace in Python:

dir(__builtins__)

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError',

'BaseException','BlockingIOError', 'BrokenPipeError', 'BufferError',

'BytesWarning', 'ChildProcessError', 'ConnectionAbortedError',

'ConnectionError', 'ConnectionRefusedError', 'ConnectionResetError',

'DeprecationWarning', 'EOFError', 'Ellipsis', 'EnvironmentError',

'Exception', 'False', 'FileExistsError', 'FileNotFoundError',

'FloatingPointError', 'FutureWarning', 'GeneratorExit', 'IOError',

'ImportError', 'ImportWarning', 'IndentationError', 'IndexError',

'InterruptedError', 'IsADirectoryError', 'KeyError', 'KeyboardInterrupt',

'LookupError', 'MemoryError', 'ModuleNotFoundError', 'NameError', 'None',

'NotADirectoryError', 'NotImplemented', 'NotImplementedError', 'OSError',

'OverflowError', 'PendingDeprecationWarning', 'PermissionError',

'ProcessLookupError', 'RecursionError', 'ReferenceError', 'ResourceWarning',

'RuntimeError', 'RuntimeWarning', 'StopAsyncIteration', 'StopIteration',

'SyntaxError', 'SyntaxWarning', 'SystemError', 'SystemExit', 'TabError',

'TimeoutError', 'True', 'TypeError', 'UnboundLocalError',

'UnicodeDecodeError', 'UnicodeEncodeError', 'UnicodeError',

'UnicodeTranslateError', 'UnicodeWarning', 'UserWarning', 'ValueError',

'Warning', 'ZeroDivisionError', '_', '__build_class__', '__debug__',

'__doc__', '__import__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__',

'__spec__', 'abs', 'all', 'any', 'ascii', 'bin', 'bool', 'bytearray',

'bytes', 'callable', 'chr', 'classmethod', 'compile', 'complex',

'copyright', 'credits', 'delattr', 'dict', 'dir', 'divmod', 'enumerate',

'eval', 'exec', 'exit', 'filter', 'float', 'format', 'frozenset',

'getattr', 'globals', 'hasattr', 'hash', 'help', 'hex', 'id', 'input',

'int', 'isinstance', 'issubclass', 'iter', 'len', 'license', 'list',

'locals', 'map', 'max', 'memoryview', 'min', 'next', 'object', 'oct',

'open', 'ord', 'pow', 'print', 'property', 'quit', 'range', 'repr',

'reversed', 'round', 'set', 'setattr', 'slice', 'sorted', 'staticmethod',

'str', 'sum', 'super', 'tuple', 'type', 'vars', 'zip']

The Python interpreter creates the built-in namespace when it starts up. This namespace remains in existence until the interpreter terminates.

The Global Namespace¶

The global namespace contains any names defined at the level of the main program. Python creates the global namespace when the main program body starts, and it remains in existence until the interpreter terminates.

Strictly speaking, this may not be the only global namespace that exists. The interpreter also creates a global namespace for any module that your program loads with the import statement.

The Local and Enclosing Namespaces¶

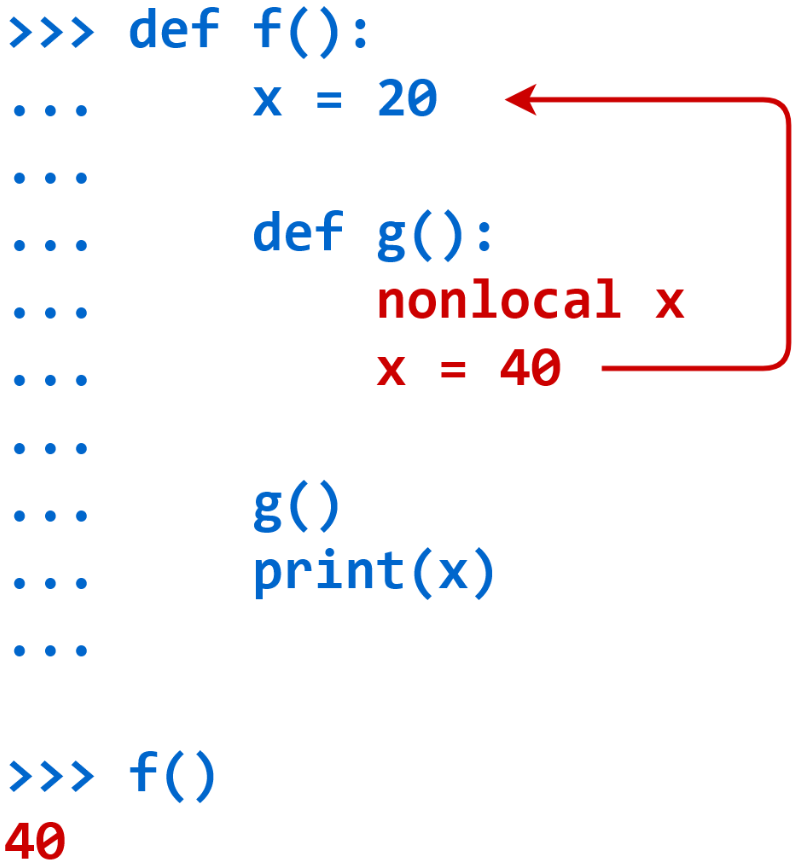

As you learned in the previous tutorial on functions, the interpreter creates a new namespace whenever a function executes. That namespace is local to the function and remains in existence until the function terminates.

Functions don’t exist independently from one another only at the level of the main program. You can also define one function inside another.

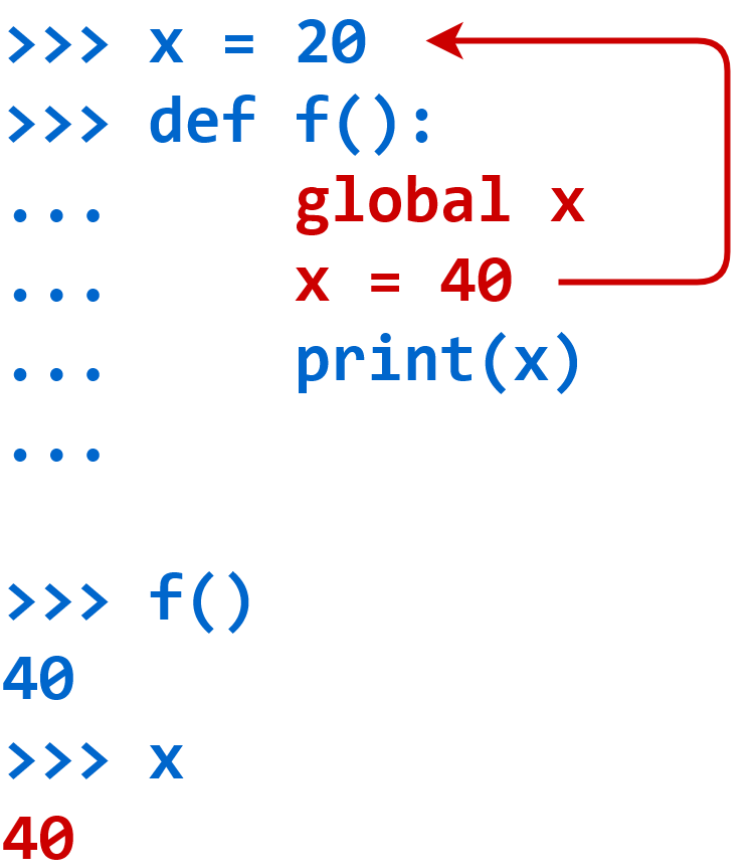

Variable Scope¶

The existence of multiple, distinct namespaces means several different instances of a particular name can exist simultaneously while a Python program runs.

As long as each instance is in a different namespace, they’re all maintained separately and won’t interfere with one another.

- Local: If you refer to

xinside a function, then the interpreter first searches for it in the innermost scope that’s local to that function. - Enclosing: If

xisn’t in the local scope but appears in a function that resides inside another function, then the interpreter searches in the enclosing function’s scope. - Global: If neither of the above searches is fruitful, then the interpreter looks in the global scope next.

- Built-in: If it can’t find

xanywhere else, then the interpreter tries the built-in scope.

Namespace dictionaries globals() and locals() :¶

n = 1

m = 2

def foo(a, b):

"""print parameters and concatenated result"""

print(globals()) # a long dictionary, including n and m

print(locals()) # {'a': 'for', 'b': ' real'}

print(a + b) # for real

foo("for", " real")

Here are 2 keywords to juggle:

y = 999

def add_two_and_print(a, b = 2):

"""This function is for demonstrating global and nonlocal"""

# modify global y

global y

print(y) # 999

y = 888

print(y) # 888

s = "foo"

print(locals()) # {'a': 10, 'b': 2, 's': 'foo'}

print("a is:", locals()["a"]) # a is: 10

return a + b

add_two_and_print(10) # 12

print(y) # 888 - y changed inside the function

Even though Python provides the global and nonlocal keywords, it’s not always advisable to use them.

Dictionaries and __slots__ Declaration¶

Here is a wonderful source if you want to dive deep. 😍

By default, Python represents each namespace with an instance of the built-in dict class (see Chapter 1.2.3) that maps identifying names in that scope to the associated objects. While a dictionary structure supports relatively efficient name look ups, it requires additional memory usage beyond the raw data that it stores (we will explore the data structure used to implement dictionaries in Chapter 10).

Python provides a more direct mechanism for representing instance namespaces that avoids the use of an auxiliary dictionary.

To use the streamlined representation for all instances of a class, that class definition must provide a class-level member named __slots__ that is assigned to a fixed sequence of strings that serve as names for instance variables.

For example, with our CreditCard class, we would declare the following:

In this example, the right-hand side of the assignment is technically a tuple .

When inheritance is used, if the base class declares __slots__ , a subclass must also declare __slots__ to avoid creation of instance dictionaries.

The declaration in the subclass should only include names of supplemental methods that are newly introduced.

Name Resolution and Dynamic Dispatch¶

When the dot operator syntax is used to access an existing member, such as obj.foo, the Python interpreter begins a name resolution process:

- Instance namespace

- Class Namespace

- Look up to Inheritance Hierarchy

- raise

AttributeError

In traditional object-oriented terminology, Python uses what is known as dynamic dispatch (or dynamic binding) to determine, at run-time, which implementation of a function to call based upon the type of the object upon which it is invoked.

This is in contrast to some languages that use static dispatching, making a compile-time decision as to which version of a function to call, based upon the declared type of a variable.

Shallow and Deep Copying¶

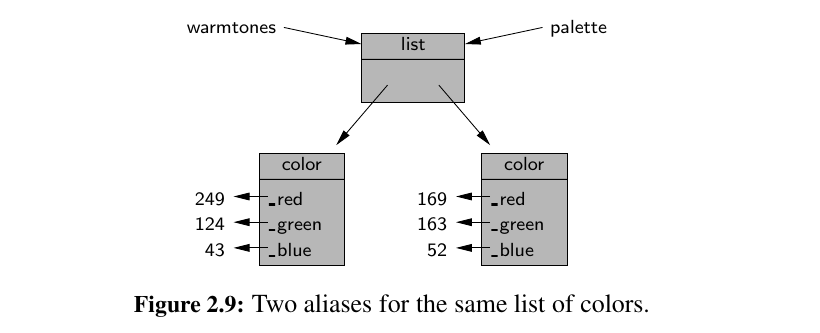

In Chapter 1, we emphasized that an assignment statement foo = bar makes the name foo an alias for the object identified as bar.

In this section, we consider the task of making a copy of an object, rather than an alias.

This is just an alias.

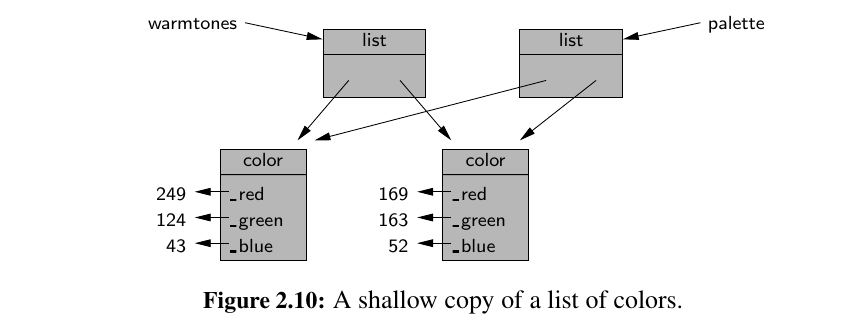

In this case, we explicitly call the list constructor, sending the first list as a parameter. This causes a new list to be created, as shown in Figure 2.10; however, it is what is known as a shallow copy

The new list is initialized so that its contents are precisely the same as the original sequence.

However, Python’s lists are referential, and so the new list represents a sequence of references to the same elements as in the first.

This is a better situation than our first attempt, as we can legitimately add or remove elements from palette without affecting warmtones. However, if we edit a color instance from the palette list, we effectively change the contents of warmtones.

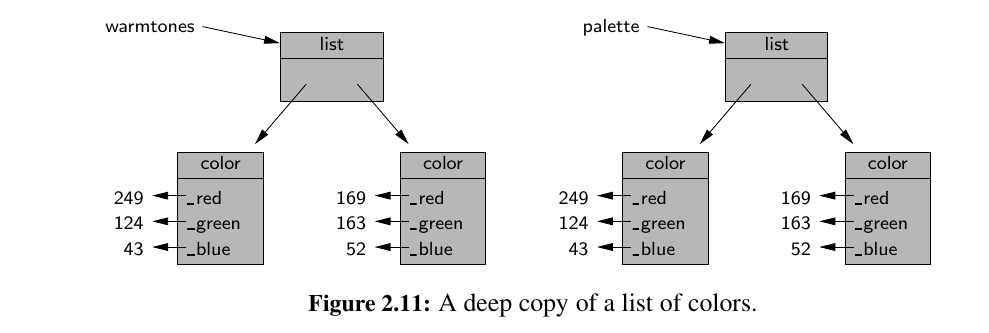

To make a deep copy, we could populate our list by explicitly making copies of the original color instances, but this requires that we know how to make copies of colors (rather than aliasing).

Python provides a very convenient module, named copy, that can produce both shallow copies and deep copies of arbitrary objects.

Here is the full code:

Now, let's move on to Algorithm Analysis! 🥰