All About Linked Lists 🎩¶

In Chapter 5 we carefully examined Python’s array-based list class, and in Chapter 6 we demonstrated use of that class in implementing the classic stack, queue, and dequeue ADTs.

Python’s list class is highly optimized, and often a great choice for storage. With that said, there are some notable disadvantages:

- The length of a dynamic array might be longer than the actual number of elements that it stores.

- Amortized bounds for operations may be unacceptable in real-time systems.

- Insertions and deletions at interior positions of an array are expensive.

In this chapter, we introduce a data structure known as a linked list, which provides an alternative to an array-based sequence (such as a Python list).

Both array-based sequences and linked lists keep elements in a certain order, but using a very different style.

An array provides the more centralized representation, with one large chunk of memory capable of accommodating references to many elements.

A linked list, in contrast, relies on a more distributed representation in which a lightweight object, known as a Node, is allocated for each element.

Each node maintains a reference to it's element and one or more references to neighboring nodes in order to collectively represent the linear order of the sequence.

We will demonstrate a trade-off of advantages and disadvantages when contrasting array-based sequences and linked lists.

Elements of a linked list cannot be efficiently accessed by a numeric index k, and we cannot tell just by examining a node if it is the second, fifth, or twentieth node in the list.

However, linked lists avoid the three disadvantages noted above for array-based sequences.

Where ?¶

You might be wondering — where is a linked list useful?

A Use/Example of Linked List (Doubly) can be Lift in the Building.

- A person have to go through all the floor to reach top (tail in terms of linked list).

- A person can never go to some random floor directly (have to go through intermediate floors/Nodes).

- A person can never go beyond the top floor (next to the tail node is assigned

None). - A person can never go beyond the ground/last floor (previous to the head node is assigned

Nonein linked list).

Insertion and deletion within the sequence in \(O(1)\) time, compared to arrays, this is great!

Singly Linked Lists¶

Let's start really small 🥰

Summary: We have head and size. Node is within the class. If there is a tail, check the edge cases.

A Singly Linked List (SLL), in its simplest form, is a collection of nodes that collectively form a linear sequence.

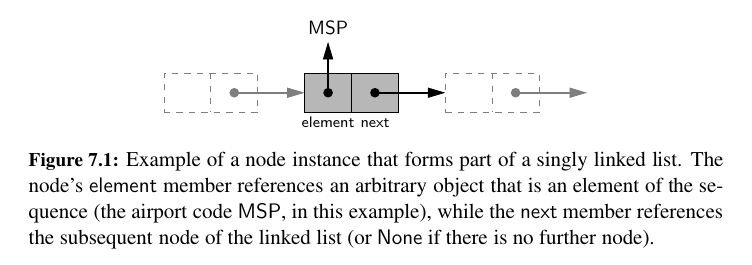

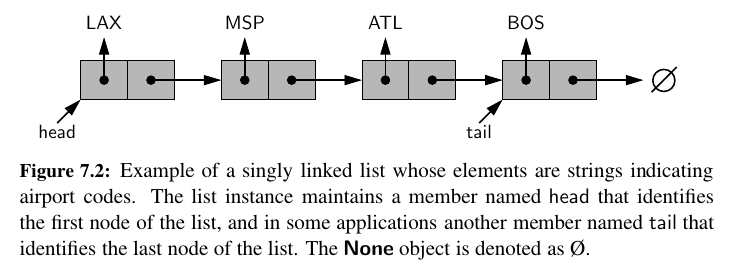

Each node stores a reference to an object that is an element of the sequence, as well as a reference to the next node of the list:

The first and last node of a linked list are known as the head and tail of the list, respectively.

Head identifies first node, tail identifies last node. 💕

By starting at the head, and moving from one node to another by following each node’s next reference, we can reach the tail of the list.

We can identify the tail as the node having None as its next reference.

This process is commonly known as traversing the linked list.

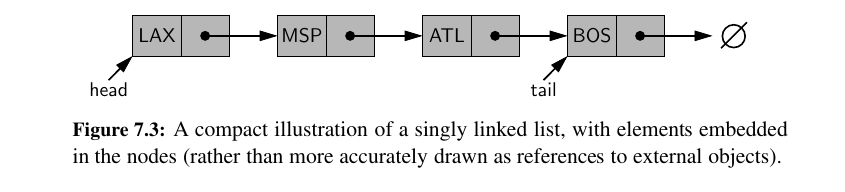

For the remainder of this chapter, we continue to illustrate nodes as objects, and each node’s “next” reference as a pointer.

However, for the sake of simplicity, we illustrate a node’s element embedded directly within the node structure, even though the element is, in fact, an independent object.

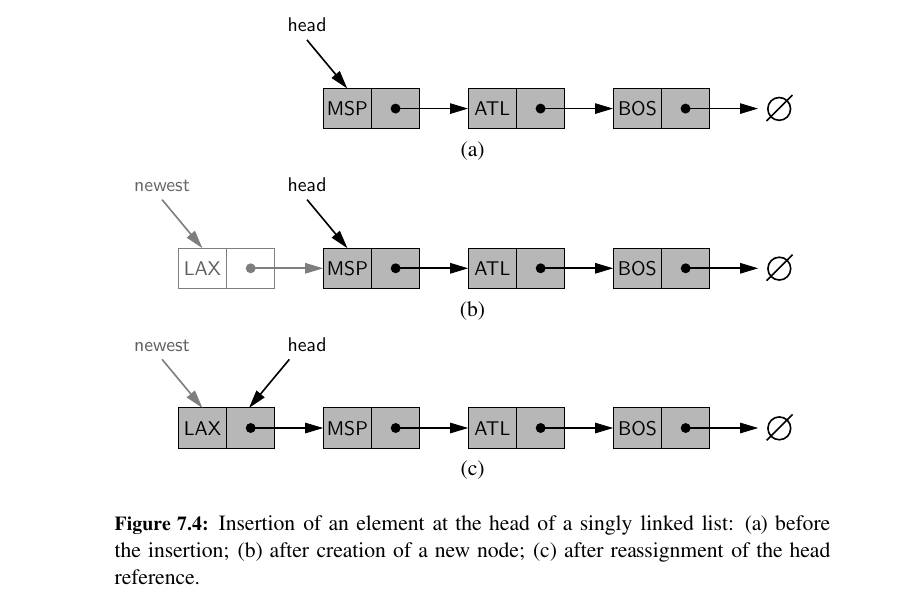

Inserting an Element at the Head of a Singly Linked List¶

There is no fixed size in a linked list, so it uses space proportionally to its current number of elements.

How do we add an element to head?

- Make a new node

- Make it point to head

- Make head point to the new node (new head)

- increment size

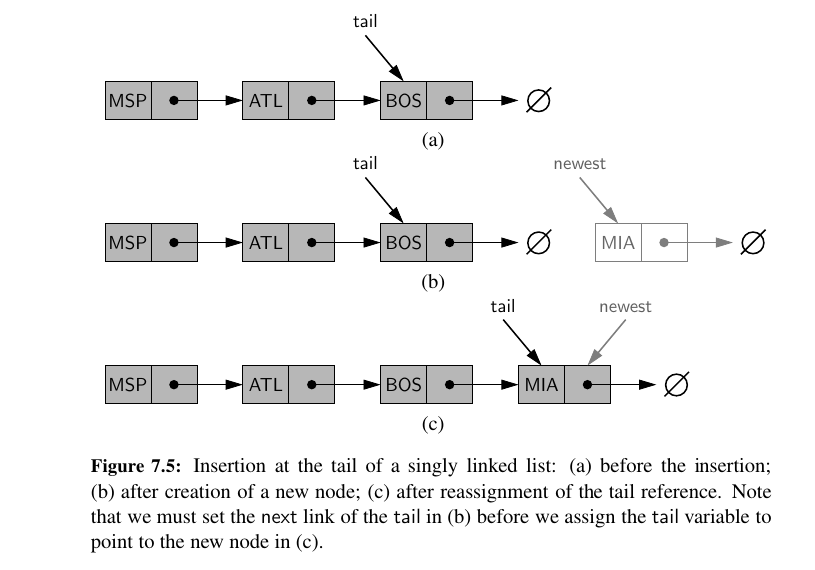

Inserting an Element at the Tail of a Singly Linked List¶

How do we add an element to the tail?

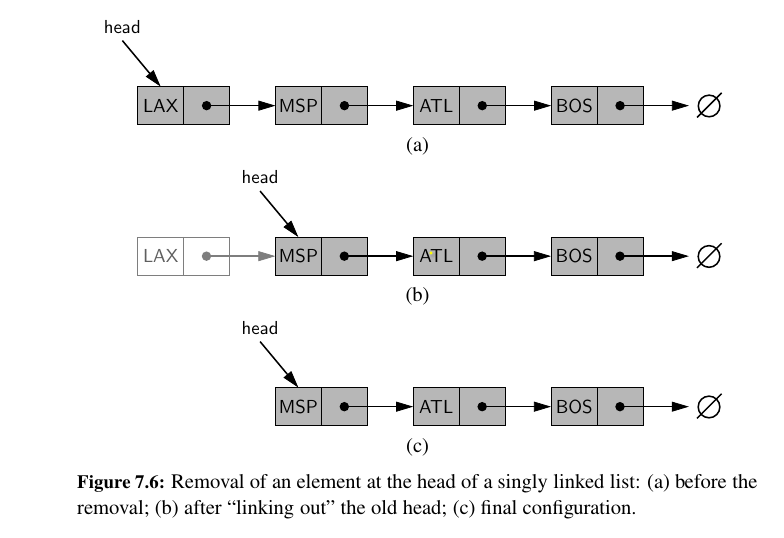

Removing an Element from a Singly Linked List - Head¶

How do we remove an element from head ?

This is essentially the reverse operation of inserting a new element to the head. 😌

Removing an Element from a Singly Linked List - Tail 🎃¶

Unfortunately, we cannot easily delete the last node of a singly linked list.

Even if we maintain a tail reference directly to the last node of the list, we must be able to access the node before the last node in order to remove the last node.

But we cannot reach the node before the tail by following next links from the tail.

The only way to access this node is to start from the head of the list and search all the way through the list (We have to traverse it all!).

But such a sequence of link-hopping operations could take a long time.

If we want to support such an operation efficiently, we will need to make our list doubly linked 😍

Linked Lists in Real World 🤨¶

In an interview if you see a question about Linked Lists, you will probably be given the most simple ListNode class like the one down below:

# Definition for singly-linked list.

class ListNode:

def __init__(self, val=0, next=None):

self.val = val

self.next = next

Using this node in a LinkedList you can solve the question you are given.

If you are not given such class, you can write it yourself. Because these are the most basic definitions for a LinkedList.

If you are ever asked to implement a stack or a queue with Linked Lists, you now what to do.

You know that for a single linked list, you can insert and remove from the head in \(O(1)\) which would be applicable for stacks.

You also know that you can insert from tail but remove from head, so for a queue, adding elements from tail and removing from head would be smarter.

Here is an example of implementing a MinStack with Linked lists:

Implementing a Stack with a Singly Linked List¶

This part is just for practice.

In designing such an implementation, we need to decide whether to model the top of the stack at the head or at the tail of the list. Where should the head be?

We learned that we can efficiently add and remove from the head, so top of the stack should be the Linked List head!

Because that is what we do in a stack. We insert at top, we remove from top. That is it!

There is clearly a best choice here; we can efficiently insert and delete elements in constant time only at the head. Since all stack operations affect the top, we orient the top of the stack at the head of our list.

Here is the code:

Here is the analysis of our operations:

| Method | Running Time |

|---|---|

S.push(e) |

\(O(1)\) |

S.pop() |

\(O(1)\) |

S.top() |

\(O(1)\) |

len(S) |

\(O(1)\) |

S.is_empty() |

\(O(1)\) |

All bounds are worst case and space usage is \(O(n)\) where n is the current number of elements in the stack.

Implementing a Queue with a Singly Linked List¶

This is also just for practice.

What does a queue do? It adds elements, enqueues them from the back and pop or remove or dequeue them from the front.

So clearly, we need to set our linked Lists so that the head is the front of the queue, and back is the end of the queue. We can enqueue in constant time in the queue, we can dequeue from front in constant time as well.

The natural orientation for a queue is to align the front of the queue with the head of the list, and the back of the queue with the tail of the list, because we must be able to enqueue elements at the back, and dequeue them from the front.

Here is the code:

In this implementation, we had to accurately maintain the _tail reference.

In terms of performance, the LinkedQueue is similar to the LinkedStack in that all operations run in worst-case constant time, and the space usage is linear in the current number of elements.

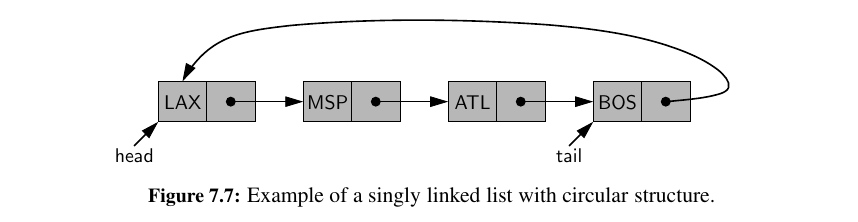

Circularly Linked Lists 😯¶

The array approach of ours for circularity was just and abstraction with the usage of modulo arithmetic.

With pointers we can actually make circular Linked Lists. 🥰

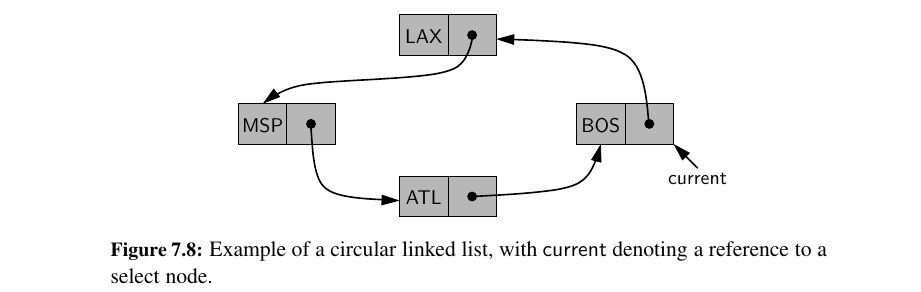

A circularly linked list provides a more general model than a standard linked list for data sets that are cyclic, that is, which do not have any particular notion of a beginning and end. Here is a more symmetric illustration to the same Circular Linked List:

Even though a circularly linked list has no beginning or end, per se, we must maintain a reference to a particular node in order to make use of the list. We use the identifier current to describe such a designated node.

Round-Robin Schedulers¶

This part is just for training.

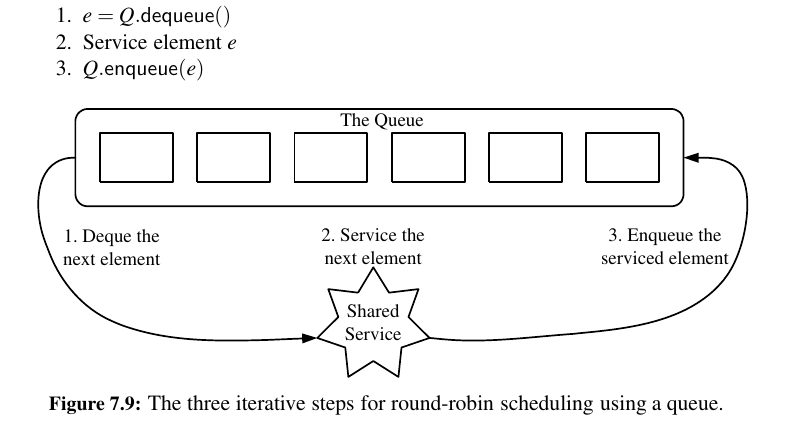

To motivate the use of a circularly linked list, we consider a round-robin scheduler, which iterates through a collection of elements in a circular fashion and “services” each element by performing a given action on it.

Such a scheduler is used, for example, to fairly allocate a resource that must be shared by a collection of clients.

For instance, round-robin scheduling is often used to allocate slices of CPU time to various applications running concurrently on a computer.

We can do this operation better in the following way:

With a CircularQueue class that supports the entire queue ADT, together with an additional method, rotate(), that moves the first element of the queue to the back (A similar method is supported by the deque class of Python’s collections module - collections.deque).

With this operation, a round-robin schedule can more efficiently be implemented by repeatedly performing the following steps:

- Service element

Q.front() Q.rotate()

Implementing a Queue with a Circularly Linked List¶

This is for training as well.

We only need _tail pointer because we know the _head can be found by following the _tail's next reference. We will have a rotate method as we expect.

Here is the code:

Here is the collections.deque rotate method:

from collections import deque

a = deque()

a.append(3)

a.append(4)

a.append(5)

print(a) # dequeue([3,4,5])

a.rotate()

print(a) # dequeue([4,5,3])

Doubly Linked Lists 🏯¶

In a singly linked list, each node maintains a reference to the node that is immediately after it.

We emphasized that we can efficiently insert a node at either end of a singly linked list, and can delete a node at the head of a list, but we are unable to efficiently delete a node at the tail of the list. 😕

More generally, we cannot efficiently delete an arbitrary node from an interior position of the list if only given a reference to that node, because we cannot determine the node that immediately precedes the node to be deleted (yet, that node needs to have its next reference updated).

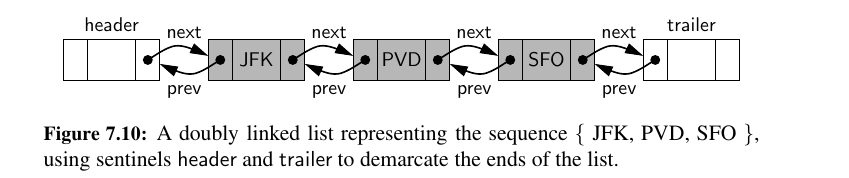

To provide greater symmetry, we define a linked list in which each node keeps an explicit reference to the node before it and a reference to the node after it.

Such a structure is known as a Doubly Linked List. (DLL) 💕

We continue to use the term next for the reference to the node that follows another, and we introduce the term prev for the reference to the node that precedes it.

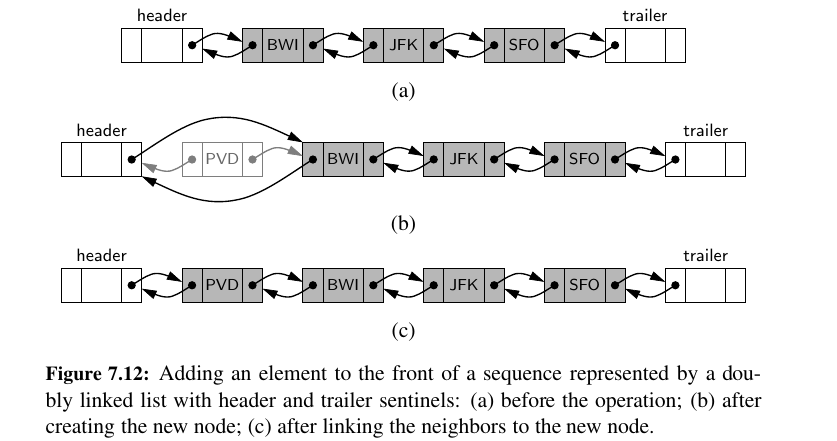

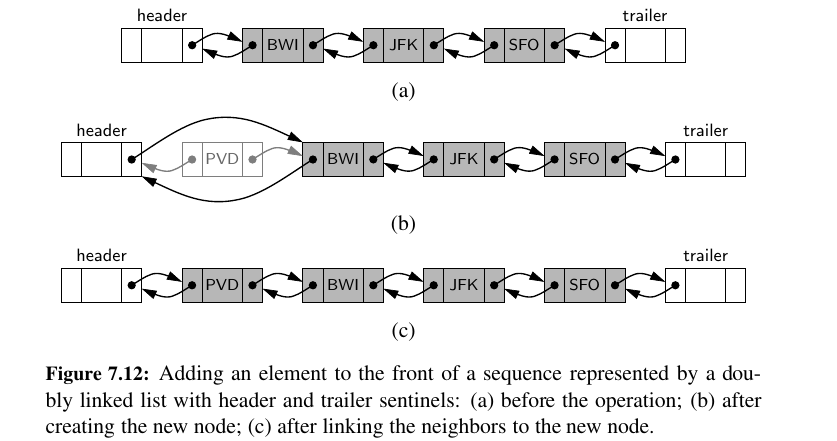

Header and Sentinels 🤔¶

In order to avoid some special cases when operating near the boundaries of a doubly linked list, it helps to add special nodes at both ends of the list: a header node at the beginning of the list, and a trailer node at the end of the list.

These “dummy” nodes are known as sentinels (or guards), and they do not store elements of the primary sequence.

When using sentinel nodes, an empty list is initialized so that the next field of the header points to the trailer, and the prev field of the trailer points to the header; the remaining fields of the sentinels are irrelevant (presumably None, in Python).

Although we could implement a doubly linked list without sentinel nodes (as we did with our singly linked list in Chapter 7), the slight extra space devoted to the sentinels greatly simplifies the logic of our operations.

Most notably, the header and trailer nodes never change—only the nodes between them change.

Inserting and Deleting with a Doubly Linked List¶

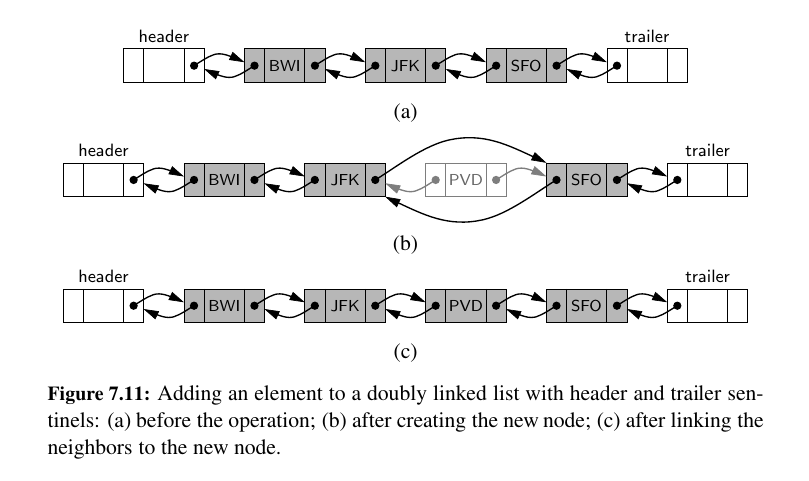

When a new element is inserted at the front of the sequence, we will simply add the new node between the header and the node that is currently after the header.

Here is how you insert to middle'ish position:

Here is how you insert at front:

The deletion of a node, proceeds in the opposite fashion of an insertion.

The two neighbors of the node to be deleted are linked directly to each other, thereby bypassing the original node. As a result, that node will no longer be considered part of the list and it can be reclaimed by the system.

Here is how you delete from a node:

Basic Implementation of a Doubly Linked List¶

We begin by providing a preliminary implementation of a doubly linked list, in the form of a class named _DoublyLinkedBase.

We intentionally name the class with a leading underscore because we do not intend for it to provide a coherent public interface for general use.

We will see that linked lists can support general insertions and deletions in \(O(1)\) worst-case time, but only if the location of an operation can be succinctly identified.

With array-based sequences, an integer index was a convenient means for describing a position within a sequence.

However, an index is not convenient for linked lists as there is no efficient way to find the jth element; it would seem to require a traversal of a portion of the list.

The constructor instantiates the two sentinel nodes and links them directly to each other. We maintain a _size member and provide public support for __len__ and is_empty so that these behaviors can be directly inherited by the subclasses.

Here is the code:

The other two methods of our class are the nonpublic utilities, _insert_between and _delete_node.

Implementing a Deque with a Doubly Linked List¶

This part is just for training.

Tip

The double-ended queue (deque) ADT was introduced in Chapter 6.

With an array-based implementation, we achieve all operations in amortized \(O(1)\) time, due to the occasional need to resize the array.

With an implementation based upon a doubly linked list, we can achieve all deque operation in worst-case \(O(1)\) time.

Here is the code:

The Positional List ADT¶

Warning

I have not bumped into a Data Structure like this one in my work, so far. This might be a little too much for diving deep and might be not necessary for beginners.

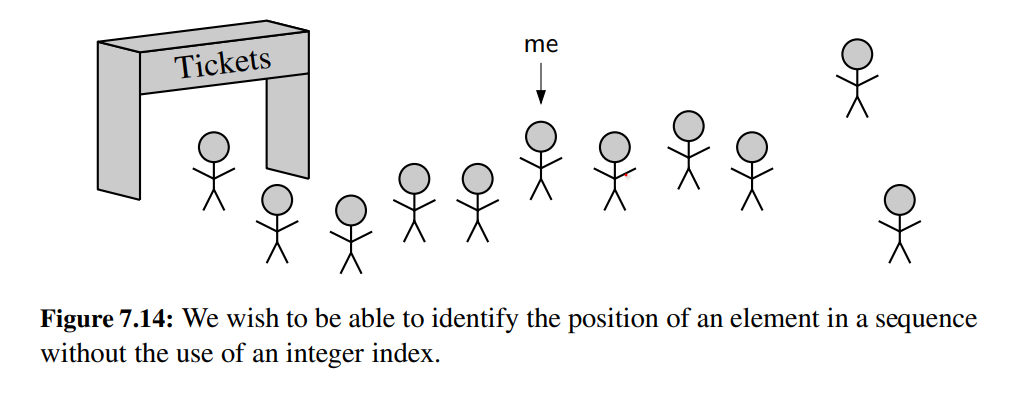

The abstract data types that we have considered thus far, namely stacks, queues, and double-ended queues, only allow update operations that occur at one end of a sequence or the other.

Although we motivated the FIFO semantics of a queue as a model for customers who are waiting to speak with a customer service representative, or fans who are waiting in line to buy tickets to a show, the queue ADT is too limiting.

What if a waiting customer decides to hang up before reaching the front of the customer service queue?

Or what if someone who is waiting in line to buy tickets allows a friend to “cut” into line at that position?

We would like to design an abstract data type that provides a user a way to refer to elements anywhere in a sequence, and to perform arbitrary insertions and deletions.

A Word Processor¶

As another example, a text document can be viewed as a long sequence of characters.

A word processor uses the abstraction of a cursor to describe a position within the document without explicit use of an integer index, allowing operations such as “delete the character at the cursor” or “insert a new character just after the cursor.”

Furthermore, we may be able to refer to an inherent position within a document, such as the beginning of a particular section, without relying on a character index (or even a section number) that may change as the document evolves.

A Node Reference as a Position?¶

One of the great benefits of a linked list structure is that it is possible to perform O(1)-time insertions and deletions at arbitrary positions of the list, as long as we are given a reference to a relevant node of the list.

It is therefore very tempting to develop an ADT in which a node reference serves as the mechanism for describing a position. In fact, our _DoublyLinkedBase class has methods insert between and delete node that accept node references as parameters.

However, such direct use of nodes would violate the object-oriented design principles of abstraction and encapsulation.

There are several reasons to prefer that we encapsulate the nodes of a linked list, for both our sake and for the benefit of users of our abstraction.

• It will be simpler for users of our data structure if they are not bothered with unnecessary details of our implementation, such as low-level manipulation of nodes, or our reliance on the use of sentinel nodes.

• We can provide a more robust data structure if we do not permit users to directly access or manipulate the nodes. In that way, we ensure that users cannot invalidate the consistency of a list by mismanaging the linking of nodes.

• By better encapsulating the internal details of our implementation, we have greater flexibility to redesign the data structure and improve its performance. In fact, with a well-designed abstraction, we can provide a notion of a non-numeric position, even if using an array-based sequence.

For these reasons, instead of relying directly on nodes, we introduce an independent position abstraction to denote the location of an element within a list, and then a complete positional list ADT that can encapsulate a doubly linked list.

The Positional List Abstract Data Type¶

To provide for a general abstraction of a sequence of elements with the ability to identify the location of an element, we define a positional list ADT as well as a simpler position abstract data type to describe a location within a list.

A position acts as a marker or token within the broader positional list.

...

TODO: This is not urgent. Will be revisited.

...

Sorting a Positional List¶

TODO: This is not urgent. Will be revisited.

Case Study: Maintain Access Frequencies¶

The positional list ADT is useful in a number of settings.

For example, a program that simulates a game of cards could model each person’s hand as a positional list. Since most people keep cards of the same suit together, inserting and removing cards from a person’s hand could be implemented using the methods of the positional list ADT, with the positions being determined by a natural order of the suits.

Likewise, a simple text editor embeds the notion of positional insertion and deletion, since such editors typically perform all updates relative to a cursor, which represents the current position in the list of characters of text being edited.

...

TODO: This is not urgent. Will be revisited.

...

Using a Sorted List:¶

...

TODO: This is not urgent. Will be revisited.

...

Using a List with the Move-to-Front Heuristic¶

...

TODO: This is not urgent. Will be revisited.

The Trade-Offs with the Move-to-Front Heuristic¶

...

Implementing the Move-to-Front Heuristic in Python¶

...

Link Based vs Array Based Sequences 😍¶

This part is REALLY important because it summarizes everything we've learned.

We close this chapter by reflecting on the relative pros and cons of array-based and link-based data structures that have been introduced thus far.

The dichotomy between these approaches presents a common design decision when choosing an appropriate implementation of a data structure.

There is not a one-size-fits-all solution, as each offers distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of Array-Based Sequences¶

• O(1) access time.

• Fewer CPU operations compared to the overhead of linked lists.

• Lower memory usage.

Arrays provide \(O(1)\)-time access to an element based on an integer index.

The ability to access the \(kth\) element for any k in \(O(1)\) time is a hallmark advantage of arrays.

In contrast, locating the \(kth\) element in a linked list requires \(O(k)\) time to traverse the list from the beginning, or possibly \(O(n − k)\) time, if traversing backward from the end of a doubly linked list.

Even when operations have the same asymptotic complexity, arrays are typically faster due to lower constant factors.

For example, enqueueing in an ArrayQueue involves:

- An arithmetic index calculation,

- A simple increment, and

- Storing a reference in the array.

Compare that with LinkedQueue, which requires:

- Instantiating a new node,

- Linking it to the existing nodes, and

- Then incrementing the size.

Both are \(O(1)\) operations, but the linked version requires more CPU work — especially due to the object allocation overhead.

Both array-based lists and linked lists are referential structures, so the primary memory for storing the actual objects that are elements is the same for either structure. What differs is the auxiliary amounts of memory that are used by the two structures.

For an array-based container of \(n\) elements, a typical worst case may be that a recently resized dynamic array has allocated memory for \(2n\) object references. With linked lists, memory must be devoted not only to store a reference to each contained object, but also explicit references that link the nodes.

So a singly linked list of length n already requires \(2n\) references (an element reference and next reference for each node). With a doubly linked list, there are \(3n\) references. 😮

Advantages of Link-Based Sequences¶

• Worst-case time bounds are not amortized (important for real-time systems)

• \(O(1)\) time insertions and deletions at arbitrary positions (great for cursor based editing - Text Editor).

Link-based structures provide worst-case time bounds for their operations. This is in contrast to the amortized bounds associated with the expansion or contraction of a dynamic array. When many individual operations are part of a larger computation, and we only care about the total time of that computation, an amortized bound is as good as a worst-case bound precisely because it gives a guarantee on the sum of the time spent on the individual operations.

However, if data structure operations are used in a real-time system that is designed to provide more immediate responses (e.g., an operating system, Web server, air traffic control system), a long delay caused by a single (amortized) operation may have an adverse effect.

Link-based structures support \(O(1)\)-time insertions and deletions at arbitrary positions.

The ability to perform a constant-time insertion or deletion with the PositionalList class, by using a Position to efficiently describe the location of the operation, is perhaps the most significant advantage of the linked list.

This is in stark contrast to an array-based sequence. Ignoring the issue of resizing an array, inserting or deleting an element from the end of an array based list can be done in constant time.

However, more general insertions and deletions are expensive. For example, with Python’s array-based list class, a call to insert or pop with index k uses \(O(n − k + 1)\) time because of the loop to shift all subsequent elements.

As an example application, consider a text editor that maintains a document as a sequence of characters.

Although users often add characters to the end of the document, it is also possible to use the cursor to insert or delete one or more characters at an arbitrary position within the document.

If the character sequence were stored in an array-based sequence (such as a Python list), each such edit operation may require linearly many characters to be shifted, leading to \(O(n)\) performance for each edit operation.

With a linked-list representation, an arbitrary edit operation (insertion or deletion of a character at the cursor) can be performed in \(O(1\)) worst-case time, assuming we are given a position that represents the location of the cursor.

You are doing incredible! Let's move on to Trees 🌳